The Broken Heart of a Dandy

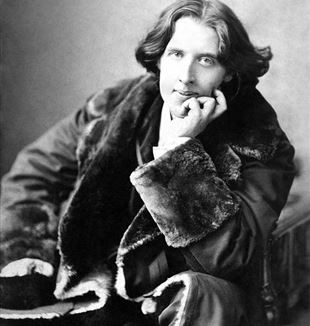

Everyone knows of his extravagance; few know of his suffering, his relationship with sin and beauty, or his deathbed conversion. An exhibit at the London Encounter has been dedicated to Oscar Wilde, and it offers a portrait of “a soul” and its hope.Oscar Wilde. It’s a name that often triggers only vague memories from high school or, at most (and depending on your allegiances), provokes either distaste or sounds of approval. During his life, in which he was a (voluntary) hostage to his reputation as a “dandy” devoted to pleasure, Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) amidst the dry English society of the end of the 1800s. He possessed an exaggerated taste for clothing and a razor-sharp wit. His aphorisms are unforgettable, for example: “I love talking about nothing; it’s the only thing I know anything about.” He spent his life chasing success and fortune, painstakingly constructing a mask that continues even unto today which misleads those who don’t look carefully.

Outside of literary circles, few know about Wilde’s inglorious end: how he was violently knocked from his pedestal by a hypocritical society that was ready to forgive anything except a scandal. Very few know about (or remember) his public shaming, the trial and prison sentence. Officially, the charge was sodomy, but perhaps his true “crime” can really be found in his fierce criticism of the materialism of his contemporaries. His conviction was followed by two interminable years in Her Majesty’s prisons, where he ended up writing two of his most beautiful works,De Profundis and The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Also little-known are Wilde’s infatuation with the Catholic Church–an interest, first stoked at John Henry Newman’s Oxford, that stubbornly persisted throughout his tormented life–and his deathbed conversion in the squalor of a cheap Paris hotel. These are not the only aspects of Oscar Wilde’s life that are not widely known: anyone who has read his fairy tales, or The Portrait of Dorian Gray, cannot help but perceive something true and luminous that defies both his followers’ and his critics’ reductions.

Few are those who recognize or dare to admit it, but among them we ought to cite a critic above all suspicion, James Joyce, who in a harsh critique of Dorian Gray writes: “Here we touch the pulse of Wilde’s art–sin. He deceived himself into believing that he was the bearer of the good news of neo-paganism to an enslaved people. His own distinctive qualities [...] he placed at the service of a theory of beauty that, according to him, was to bring back the Golden Age and the joy of the world’s youth. But if some truth adheres to his subjective interpretations of Aristotle, to his restless thought that proceeds by sophisms rather than syllogisms, [...] at its very base is the truth inherent in the soul of Catholicism: that man cannot reach the divine heart except through that sense of separation and loss called sin.” It is sin, then, that is the “pulse” of Wilde’s art, along with suffering.

A Heart Made of Lead

Wilde’s Happy Prince, in the fairy tale by the same name, tellingly says, “When I was alive and had a human heart [...] I did not know what tears were, for I lived in the Palace of Sans-Souci, where sorrow is not allowed to enter. In the daytime I played with my companions in the garden, and in the evening I led the dance in the Great Hall. Round the garden ran a very lofty wall, but I never cared to ask what lay beyond it, everything about me was so beautiful. My courtiers called me the Happy Prince, and happy indeed I was, if pleasure be happiness. So I lived, and so I died. And now that I am dead they have set me up here, so high that I can see all the ugliness and all the misery of my city, and though my heart is made of lead, yet I cannot choose but to weep.”

Sin and suffering are key themes in Wilde’s writing, as is the heart of his human experience. His life was one prolonged attempt to, on the one hand, kill his “soul,” which, like the portrait of Dorian Gray, reveals to him the signs of his sin, and, on the other hand, to flee from the experience of suffering. In De Profundis he writes, “I used to live entirely for pleasure. I shunned suffering and sorrow of every kind. I hated both. I resolved to ignore them as far as possible. [...] My mother, who knew life as a whole, used to often quote Goethe’s lines [...]. ‘Who never ate his bread in sorrow, Who never spent the midnight hours weeping and waiting for the morrow–He knows you not, ye heavenly powers.’ I did not understand. I remember quite well how I used to tell her that I did not want to eat my bread in sorrow. [...] I had no idea that it was one of the special things that the Fates had in store for me.”

His Oldest Son

Sin and sorrow, which Wilde was destined to live through, were not, however, the last word; they were, instead, a road. They were a road to the experience of beauty that Wilde longed for throughout his life. As many have noted, Wilde’s theory of aesthetics was not merely a run-of-the-mill hedonism; if anything, it was an attempt to redeem reality through art, beauty, and imagination. It was a sad attempt that over the long term engendered a distrust in reality and a schizophrenic alienation that couldn’t help but have tragic results. For Wilde, the beginning of his road of sorrow was like a return to reality, which continued in the experience of being stripped of everything and, finally, became prayer. It was a tiny opening through which “salvation” could come. “

But I still had my children [After the scandal, Wilde was never again able to see Cyril, his beloved oldest son]. Suddenly they were taken away from me by law. It was a blow so appalling that I did not know what to do, so I flung myself on my knees, and bowed my head, and wept, and said, ‘The body of a child is as the body of the Lord: I am worthy of neither.’ That moment seemed to save me.” The image that best represents Wilde’s human journey is a broken heart. Wilde later spoke of how his heart was broken by the years in prison, along with the mysterious link between sorrow and love and the discovery that, by humbly accepting sorrow, a man can truly become himself and find his “soul.” Pain can be rebelliously refused or stoically tolerated, but only a broken heart opens up to the possibility of seeing the hypothesis of salvation on the horizon of a man’s life, as Wilde writes in the heartrending Ballad of Reading Gaol: “Ah! happy day they whose hearts can break / And peace of pardon win! / How else may man make straight his plan / And cleanse his soul from Sin? / How else but through a broken heart / May Lord Christ enter in?” Wilde’s Christ is gnostic, one who is human but not God, but One in front of whom he would eventually bow down, converting in the last moments before death. It is a Christ who teaches nothing, but “makes things change”; who unites suffering and beauty in Himself, redeeming both, a Christ that purifies the “ugliness of sin” and reveals the “beauty of sorrow” to those who come into contact with His person. This was the true discovery of Wilde’s life, which was mysteriously prophesied by his writing, especially in his Happy Prince.

“Beauty and Sorrow” is the title of the exhibition that the CL community in England prepared for the second annual London Encounter (June 6, 2015). At the heart of the exhibit is the story of the Happy Prince, told through original illustrations drawn by American illustrator Brad Holland who has worked for such publications as Time, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair and The New York Times.

To Open the Door

The fairy tale, written during the happiest time of Wilde’s life, tells of a wealth that strips itself away to become visible only to the eyes of God and of a broken heart welcomed into Paradise. It’s a prophecy, but it also expresses the hope that those who worked on the exhibition said were the greatest gifts of their encounter with Wilde. As Rowan Williams, Patron of this year’s London Encounter, wrote in the preface of a new edition of The Happy Prince (published by Edizioni Nuages, Milan): “Written with a musical clarity that still demands attention, the story opens the door to a vision of the truth that Wilde himself did not have the courage to believe in completely until the end of his life. The story tells us, though, that Wilde earnestly desired that this vision was true even before he understood–with his own heart broken–that it was true. The story still has the power to open that door (and that desire) to many readers.”