The Rebel Returns Home

Walter Salles’ film On The Road affords an opportunity to read the novel of the Beat Generation by Jack Kerouac, a figure critics have deemed “icon of an era.” His is the story of a man who did not want to lose himself to conform to society.On December 21st, the film On the Road, directed by Walter Salles and presented at the Cannes Film Festival, will be released. It is the cinematographic adaptation of the famous novel by Jack Kerouac, On the Road, the book about the Beat Generation that gained a cult-following among youth of the Sixties and represents a “turning point” in American literature for the unique way that it translated rapid-fire speaking into writing.

Condemnation of this kind of writing came from many quarters, including from the highly respected writer, Truman Capote, who scathingly quipped about the Beat Generation, “None of these people have anything interesting to say and none of them can write, not even Mr. Kerouac... It isn’t writing at all–it’s typing.” But here, the author of the masterpiece In Cold Blood was badly mistaken, because Kerouac had meditated a long time before writing On the Road–and then he rewrote and rewrote. Probably inspired by writers such as Mark Twain, Jack London (author of The Road), and Ernest Hemingway, Kerouac pushed himself beyond, reaching a further frontier, to the point of distorting punctuation itself.

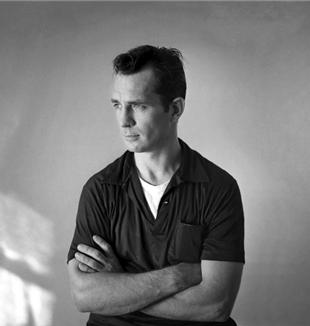

The rise of a hipster. The motivation for this literary “revolution” was not casual; rather, it was the vehicle for an even more radical rebellion against the conformist world that surrounded him, and even against the industrial-editorial machine that wanted to pigeon-hole him as an “icon of an era,” a stereotype, caging and encapsulating him as the spokesman for a one-way rebellion in a specific historical context. The real Jack Kerouac is more complex than the writer propagandized by the editorial machine, and it is to be hoped that Salles’ film does not present him in a limited way, as just an emblem of the Beat Generation.

A recollection of Kerouac from 1951 is valuable for understanding the man and the writer: “A Ritz Yale Club party where I went with a kid in a leather jacket, I was wearing one too, and there were hundreds of kids in leather jackets instead of big tuxedo Clancy millionaires... cool, and everybody was smoking marijuana, wailing a new decade in one wild crowd.” Herein lies a point that often is not pursued. It was precisely to flee this new WASP conformism in post-war America, the updated edition of capitalist-Calvinist society, in which the notion of time and work was brutally monetized, it was in the face of that moralistic and hypocritical society, that Kerouac wrote On the Road, describing the precarious life that Jack London had already written about in The Road. But it was a rebellion against conventionality in every era, against every era’s standardization, against societies that become profoundly hypocritical, that no longer want to find an authentic sense and meaning in life. It was in the face of that image of standardization, that self-delusion, that the young and sensitive Jean-Louis Lebris de Kerouac, born in Lowell, Massachusetts, of a French Canadian family, chose to write On the Road. Through it, he lived, deep down, his awareness of life’s precariousness with striking sensitivity, flavored by limitless sensuality, a river of alcohol, and continuous drug abuse.

The main character of On the Road, Dean Moriarty (who, in real life was Kerouac’s friend, Neal Cassady), was a prototype of what came to be called a hipster, a person who abandons all false security, to live every moment of his existence with white-hot intensity, burning in a flame of pure energy. The Moriarity-Cassady figure was like Marlon Brando in Wild One or James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, embodying a condition of life, an even corporeal expressivity, a melancholy challenge, an ironic, paradoxical, ostentatious opposition to the WASP prototype of the new American society.

The sweetest month. This leads to the question of what message On the Road can have for today’s generations, so removed from that historical context. What meaning is there in Kerouac’s rebellion? Is it a destructive rebellion as an end unto itself? Is it a protest ahead of its time that would lead to the famous youth protests of the 1960s? Who is Kerouac? Is he the prophet of the hippies, as has often been asserted? Everyone wanted to categorize him like this.

The surprise comes from a more reflective reading of On the Road and of the life of Jack Kerouac. It is not contradictory to say that in Kerouac one sees heart-thawing nostalgia for a lost tradition, a rebellion against a society that abandons the meaning of life, that renounces its roots.

Some statements that Kerouac made were, on more than one occasion, emblematic. When he was called a Buddhist, he responded in no uncertain terms that he was “a strange solitary crazy Catholic mystic.” And always, in the most searing moments of his existence, he would think of “returning home.” He wrote, “October is the sweetest month. In October everyone goes home.” He, the rebel, propagandized as the precursor of the hippies or a certain left-wing American stream, always wanted to return home, to find once again his roots, the tradition in which he grew up, even in the midst of wrenching pain and tragedies, like the death of his younger brother, the untimely death of his father, and the somewhat selfish sensitivity of a mother who perhaps wanted a famous son more for her own sake than for his.

To counter the stereotype in which the editorial industry had boxed him, Kerouac minced no words in a Paris Review interview: “I am so busy interviewing myself in my novels, and have been so busy writing down these self-interviews, that I don’t see why I should draw breath in pain every year for the last ten years to repeat and repeat to everybody who interviews me (hundreds of journalists, thousands of students) what I’ve already explained in the books themselves. It begs sense.”

We’ll have to wait to see whether Walter Salles’ film brings something new to the current cultural dialogue. At the moment, we cannot make a judgment on the film, but we can offer a word of advice to young people: look past the propaganda and type-casting with which the cultural industry of standardized societies describes the “great rebels,” paradoxically subverting them to the service of cultural standardization.

“No one would understand him.” Jack Kerouac is important because he was a rebel who sought, in an artificial social context, the profound meaning of life and aspired only to a simple existence, marked by certainties and evidence of truth. Mary Carney, the first girl who loved him, a forgotten witness to the real Jack Kerouac, sheds some light on his identity: “He was a good, sweet boy, and the people of Lowell did not understand him. They never understood him. No one ever reads here. They haven’t even given him a plaque. Jack was so sensitive; all he wanted was a house and a job on the railroad. Jack always told me everything. But no one would understand, so I won’t say anything more, and I’m keeping my word. Anyway, no one listens to you.”

Perhaps the film about this burned-out existence of a rebel against an invasive power–whose sweet and ruthless persuasion reduces one’s desire for a true life–can give us back the Kerouac who wrote On the Road to guarantee for him a “return home,” to his home.