The Last Cry

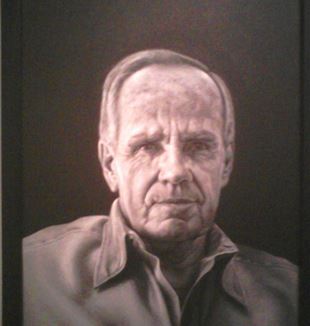

In the third installment of our literary journey accompanying "The Religious Sense," we present novelist Cormac McCarthy, in whose work "the human being is not dead." He transforms into words not so much a worldview as a "density" of experience."The rain stopped and the night cleared and the moon that was already risen raced among the high wires by the highway side like a single silver music note burning in the constant and lavish dark." (All the Pretty Horses)

Only an extraordinary writer can conceive of a line like this. Not so much because of the metaphor of the musical note–these are the "tools of the trade"–and not even because of the "constant and lavish dark"–personal opinions of the writer–but for that notation thrown there as if by chance: "the moon that was already risen raced among the high wires." It's just stopped raining and the high wires are wet. The protagonist of the novel looks out of the window of a truck. The moon isn't visible, because it's on the other side of the truck. Only the moon's reflection on the wires is seen. First you didn't see it; now you see it: the moon has risen. It's just a small but meaningful example of the greatness of the writer: Cormac McCarthy.

Nine-tenths of the work of a narrator is the toil of tilling the hard earth of experience to transform it into words. Whatever the style (the journey that reality makes to become word obeys its own dynamic, which we call "invention"), there's always only one issue: the density of experience that the word manages to capture. Literature is a question of density. In this, no writer in the world is the equal of McCarthy. The ability to see what others don't see, to foresee what others can't image, is the first surprise for any reader. With each line, you run up against things that have happened a thousand times and you've never noticed, or for which you've never found the words.

Literary criticism speaks of a "visionary quality" which is something more than imagination. We see this in Leopardi (with whom McCarthy shares many points in common) when he says: "Now the air is darkening everywhere, / the sky turns blue again, and shadows / fall again from hills and roofs, / while the new moon goes white." (Saturday in the Village)

How much attention to the color of the sky, to the coming and going of shadow!

The exceptionality of a writer begins here–not with his vision of the world, not with what he thinks, but with the way he treats things (with his "morality in knowing," The Religious Sense would say), because it is here that his drama takes flesh.

Except for a few very important works, especially the masterpiece Blood Meridian (the most violent of McCarthy's books, set in the height of the epic West) and the science fiction, visionary The Road, most of McCarthy's works take place in a very precise era, between World War II and the early 1950s, when the American army requisitioned ranches, bringing to an end the period of the Wild West.

HUNGER FOR MYSTERY. The cowboys, guardians of cattle, must find a new trade (this is also portrayed in the Coen brothers' most recent film, True Grit), and end up for the most part doing bit pieces in Western films, because by now they're incapable of reintegrating into American society.

While the last cowhands reflect on their obscure tomorrow, the landscape of the West is being populated by trains, highways, cars, and pick-ups. In this precise historic moment, McCarthy identifies a decisive page of American history, the passage of an era from the great American Dream, which had unified the country, to something completely different: a sort of disintegration–between states, communities, and lifestyles that are extraneous to each other–held together by the precarious glue of the army and, later, by film and television.

In his celebrated Trilogy (All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, Cities of the Plain), the writer follows the life of some young men who rebel against the change and look for places and ways to conserve their old lifestyle–they are 14, 16 years old, but their lives are already bound forever to horses and the wild life. A tragic sentiment of Destiny accompanies their solitary and poetic existence, generating love, violence, and death.

"They are gone now. Fled, banished in death or exile, lost, undone. Over the land sun and wind still move to burn and sway the trees, the grasses. No avatar, no scion, no vestige of that people remains. On the lips of the strange race that now dwells there their names are myth, legend, dust." (The Orchard Keeper)

In an interview, McCarthy said that he didn't love writers like Proust and Henry James, who don't deal with life and death. But nature in McCarthy is populated by signs, and these signs often take on the form of alarms, warnings.

"…they swerved across the pike and shot out into blackness, the lights slapping across the upper reaches of trees standing sharply up the side of the hollow." (Ibid).

"He smoked continuously, cranking in the windshield to light a fresh cigarette from the old stub and studying in the glare of their union his shadowed muzzle in orange relief on the glass…" (Ibid).

Such details burn the page and the reader's eyes because they are precise signs that can't be taken lightly. The Western landscape takes on biblical colors, the deserts of Texas and those of Jericho merge, and in all the adventures of the protagonists, even the crudest, there is at work–often explicitly–a sapiential story line, as if all human stories were nothing other than surprising variations of the one story that embraces all: the one beginning with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and ending with the Final Judgment.The young men of McCarthy's books aren't people who resign themselves to seeing in the world only what's there. But horror, death, and the devil await these men. The new America will banish all forms of mystery.

Listen to the talk of the pimp who will kill John Grady Cole (the protagonist of the Trilogy, in love with a young prostitute), in Cities of the Plain: "In his dying perhaps the suitor will see that it was his hunger for mysteries that has undone him. Whores. Superstition. Finally death. For that is what has brought you here. That is what you were seeking. […] that is what has brought you here and will always bring you here. Your kind cannot bear that the world be ordinary. That it contains nothing save what stands before one. […] your world totters upon an unspoken labyrinth of questions. And we will devour you, my friend. You and all your pale empire."

REGULAR EVIL. In his most recent works, McCarthy has taken a further step in his reflection. In another masterpiece, No Country for Old Men, the great writer articulates his own vision of man and history. Here, there are three protagonists: a young delinquent, a sheriff, and a terrible assassin, come from outside, whose name–Chigurh–in and of itself is inhuman, and who reasons according to a standard that the sheriff doesn't understand.

Up to this point, the relationship between criminals and justice has been founded on a common anthropological basis: the same values (transgressed by the former; defended by the latter); the same way of reasoning. As long as an idea of community supports coexistence, America can continue living. For that matter, it was in studying the community village of New England that Alexis de Tocqueville produced Democracy in America. The schism of the community is like the cleavage of an atom: the American Man disintegrates, and in his place comes a stranger, a being without roots or memory, who can no longer distinguish between friends and enemies.

So Evil, when it presents itself, has no face: the sheriff has no instruments for capturing an assassin like Chigurh, who kills with a nail gun and leaves no one alive who can recognize him, so that there is no identikit for him. In the end, someone recognizes him, it's true, but here the horror rises before our eyes, because his figure, neither tall nor short, neither thin nor fat, regular face, everything regular, is so normal, so average that it's impossible to describe it.

The book ends with the sheriff's abdication and a moving reflection on what people today lack in being able to credibly face the challenge of good, of justice, of truth (we would say, the challenge of the heart, because our heart is the first challenge): "Where you went out the back door of that house there was a stone water trough in the weeds by the side of the house. A galvanized pipe come off the roof and the trough stayed pretty much full and I remember stopping there one time and squattin down and looking at it and I got to thinking about it. I don't know how long it had been there. A hundred years. Two hundred. You could see the chisel marks in the stone. It was hewed out of solid rock and it was about six foot long and maybe a foot and a half wide and about that deep. Just chiseled out of the rock. And I got to thinking about the man that done that. That country had not had a time of peace much of any length at all that I knew of. I've read a little of the history of it since and I aint sure it ever had one. But his man had set down with a hammer and chisel and carved out a stone water trough to last ten thousand years. Why was that? What was it that he had faith in? It wasn't that nothing would change. Which is what you might think, I suppose. He had to know better than that. I've thought about it a good deal. I thought about it after I left there with that house blown to pieces. I'm goin to say that water trough is there yet. It would of took something to move it, I can tell you that. So I think about him settin there with his hammer and his chisel, maybe just a hour or two after supper, I don't know. And I have to say that the only thing I can think is that there was some sort of promise in his heart. And I don't have no intentions of carvin a stone water trough. But I would like to be able to make that kind of promise. I think that's what I would like most of all."

People today lack that promise, that capacity to look at time, at vicissitudes, at good luck and bad luck, at the war, keeping in their eyes something more, the something that is capable of making life beautiful and livable in any situation.

THE ROAD OF HEROISM. Notwithstanding this, the human being is not dead. Realistically, McCarthy informs us that in this moment the tide of the battle between good and evil is turning for evil. This doesn't mean that the human being has been annihilated. Culture, power, riches, and educational disaster have not had the last word. The work of Cormac McCarthy possesses the power of this ultimate cry. We see this in The Road, in which what could be the last man in the world leaves with his son, without any hope of salvation after the complete destruction of the world. And yet the two go into a surreal landscape, living day by day. What moves them? The hope of surviving? Or that greater promise?

It's a question we all have to answer personally. And it's all a question of freedom. Heroism is this, and for this reason, "there's never one day that's different from the other."

The son is in front of his dying father: "'What's the bravest thing you ever did?' He spat into the road a bloody phlegm. 'Getting up this morning,' he said." But if, instead of being the last morning of the life of that man, it were a normal morning, one like the others, the conversation could be repeated just the same. What is the force that enables a man to get up in the morning as a man? This is the problem, this is the "to be or not to be." And every morning we engage in this drama. McCarthy writes: "People complain about the bad things that happen to em that they dont deserve but they seldom mention the good. About what they done to deserve them things. I don't recall that I ever give the good Lord all that much cause to smile on me. But he did."