Under the Portico of Glory

The portal of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral is like an immense “book of stone” that speaks to every pilgrim. In the Holy Year of the Journey of Santiago, a book and an exhibition explore every detail of the Romanesque masterpiece.More than an art book or a book on religious culture, this seems to be a real investigative report, conducted on one of the most famous and venerated monuments of Christian tradition: the Portico de la Gloria, open on the western façade of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Many know of the extraordinary attraction this place has generated for centuries–it is a pilgrimage destination for millions of faithful (but not exclusively). Anyone who has been there even once knows the simple ritual that accompanies the entrance into the Cathedral through this grand portal. But little is known of the meanings this monument seeks to communicate to those who enter. Like an immense book of stone, the Portico de la Gloria dialogues, speaks with the pilgrims.

So, what does it tell them?

This is the subject of the inquiry that Félix Carbó has conducted and that now, in the Holy Year of Santiago de Compostela, takes the form of a book (El Pórtico de la Gloria. Misterio y Sentido), a website, and a documentary exhibit, supported by extraordinary photographs that “flush out” details that might seem secondary but are hardly so.

Carbó begins his inquiry trying to explain an anomaly of the Portico’s history: according to historical sources, the current portal is not the original one of the Cathedral finished around 1122, as recorded in the Códice Calixtino by Aymeric Picaud, a contemporary monk and chronicler. Actually, the Portico we see is the work of the famous Maestro Matteo, who lived 50 years later, as attested by numerous documents and confirmed incontrovertibly by the Latin words carved behind the central column: “In the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1188, the day April 1, the architraves of the largest portal of the Church of Santiago were placed by Maestro Matteo.” Why would the Portico be redone after only a few decades, especially since doing so lengthened the Cathedral by a bay? Carbó’s hypothesis is that the decision was made by “those who had authority over the Cathedral construction,” having judged that the previous portal was “not adequate for representing the power of the Glory of Christ.”

Keystone

Thus Maestro Matteo enters on the scene, a figure who, judging by the documents of the time, must have enjoyed enormous prestige–if it is true that in 1168 King Ferdinando II of Leon, Galicia, and the Asturias awarded him a rich lifetime annuity. Ferdinando II was the son of Alfonso VII, nephew of Pope Callixtus II who, in 1126, instituted the Compostelan Year, a “holy year” that occurred every time the Feast of Saint James fell on a Sunday. For Santiago, it began a period of extraordinary cultural flowering that drew some of the best architects and sculptors of Europe, among others.

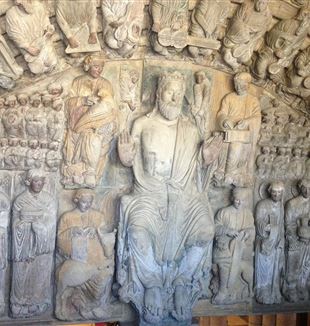

In the heart of such a vital city, the great undertaking of Maestro Matteo began. The Portico de la Gloria is a unit of rare richness and complexity, with over 200 figures; its architectonic structure imposes itself with such power that it almost becomes the center of the very church to which it serves as an entry. It is composed of three openings: on the left, the door of the Old Covenant, crowned by the representation of Limbo; on the right, that of the New Covenant, crowned by Purgatory; and, in the center, the most majestic opening, dedicated to the Glory of Christ. This central door expresses the entire meaning of the Portico, dominated by the scene of a great Christ in majesty that seems to be inspired by the Byzantine model of Christ Pantocrator. But unlike Byzantine iconography, here Christ is not isolated in His mandorla, but is surrounded by numerous figures in action. First of all, there are the four evangelists, all caught in the act of writing, like true chroniclers of a royal court. Then, there are the angels who show the symbols of the Passion. In the upper section, there is perhaps the most unexpected presence: that of the people. On the left, the people of Israel, on the right, the Christian people. “The genius of Maestro Matteo created an entirely new composition,” explains Félix Carbó. “The Christ of the Portico is a Christ Pantocrator, but a Christ with His people.” The fact of giving equal space to the Jewish people is explained with reference to the Letter to the Ephesians: “For He is our peace, He who made both [peoples] one and broke down the dividing wall of enmity” (Eph 2:14).

The certainty of a people. Another enigmatic point of the Portico is without a doubt the figure set behind the central support that divides the biggest arch. On the front of the support is the famous figure of Saint James; on the back, instead, is the kneeling figure of a penitent who is turned toward the main altar. Ancient tradition has always considered this a self-portrait of Maestro Matteo, whose popularity has even accorded him the fame of sainthood. According to ancient affirmations, the parchment scroll in his left hand once had the word “architectus.” On the same stone, an initial “f,” for “fecit”–“made it”–is still legible. Therefore, there is a strong probability that this is truly Maestro Matteo, an element almost unique in medieval sculpture, which generally tended to efface individualities in the collective dimension of the work.

At Santiago, the originality of the individual stands out as capacity to grasp more deeply a certainty that belonged to the entire people. “This image enhances the characteristics of the figure,” explains Félix Carbó, “penitent and humble before the Mystery. In a certain sense it is truly his signature.”

Matteo’s Choice

Félix Carbó’s inquiry obviously addresses a great many other issues, the meanings of which he faces one by one and almost always clarifies with certainty. At the end of his journey, the author quotes a passage from Benedict XVI’s encyclical, Spe Salvi, as the key for understanding the Portico della Gloria’s present-day relevance. The Pope says that often artists were tempted to emphasize the “ominous and frightening” aspects of the judgment over the representation of the “splendor of hope.” Maestro Matteo was one of those artists who, without hesitation, chose to give form in stone to the “splendor of hope.”