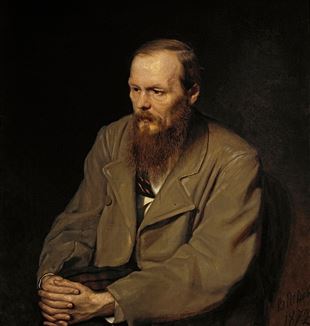

Dostoevsky and The Blows of Hope

Tatiana Kasatkina, one of the world's greatest experts on Fyodor Dostoyevsky, discusses the 'christian paradox' found in the Russian author's work.“It was not a choice of mine; I came across Dostoyevsky at the age of 11, when I read The Idiot. Since then, I have never left him; I couldn’t conceive my life without him.” Tatiana Kasatkina, 45, is a scientific collaborator at the Institute on Universal Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences and directs the Study Commission on Dostoyevsky, set up eight years ago by the Academy. So she is one of the greatest experts in the world on the writer, having edited a nine-volume collection of his works. What ties her to Dostoyevsky is more than academic interest. Since she grew up in a country that propagated atheism and had banned the Bible (“the first clandestine Bible reached me at the age of 17”), it is thanks to the author of Crime and Punishment that Kasatkina discovered the faith. “When the regime removed Dostoyevsky from the index of forbidden authors, a cover that was hiding heaven from me was lifted, and a ray of light for a whole generation appeared.” A few days ago, Kasatkina was in Italy to take part in a convention on Vasily Grossman. She spoke of hope in Dostoyevsky to a hundred or so students at Milan’s Catholic University and at the University of Florence, revealing among other things many analogies between the great Russian writer and Fr. Giussani (last April, Kasatkina presented Giussani’s book Is It Possible to Live This Way? at the Bookshop of the Spirit in Moscow). “They see things in the same way,” she said. An example? “For both of them, the heart of Christianity is the Presence of Christ; not an event confined to 2,000 years ago, but something that happens over and over again.”

Dr. Kasatkina, what is common in the experience of hope of these two people, Dostoyevsky and Giussani, so far apart in time and space?

On reflecting on this theme, I realized that the analogies are far more numerous than the differences. It is proof of the fact that Christianity, in its ultimate depth, is unitary; it produces the same fruits, and it cannot be otherwise. Fr. Giussani speaks of hope in terms of a Presence that is there and towards which we must at the same time continually tend. In other words, it shows us that God has already made his move and is waiting, humbly, for man’s move. I would say that Fr. Giussani speaks not so much and not only of the hope that man puts in something or someone, but he places the accent on God who, despite everything, continues to hope in man: “See, I stand at the door and knock. If someone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him and he with me” (Ap 3:20). And this is exactly what Dostoyevsky says, too.

In what sense?

All his work is aimed at discovering the manifestation of the image of God in man, an image that might seem terribly obscured, altered, distorted, like an icon that is blackened and dirty, but never completely spoiled; it is indelible because it is founded on that promise of fidelity: “I will keep on knocking.” He remains unchangingly faithful, and precisely this is our hope–hope in a Presence here present, now and always, at our door, waiting for our freedom. God is always available, but we rarely are. In the Diary of a Writer, Dostoyevsky admits that genuine Christians are few, too few; it seems there are no more of them left. But immediately after he asks, “What do we know about how many genuine Christians are needed so that the great hope be not stifled in the world?”

Hope, greatness, beauty… it is often said that in Dostoyevsky the greatest figures are the negative, obscure ones, while the “positive” figures are incomplete, imperfect. In other words, Dostoyevsky is seen as the genius of human despair, of the painful impossibility of making hope a reality…

I am categorically against this interpretation. The problem is rather our incapacity to see, to perceive genuine beauty–so discreet, “waiting,” as Christ is. On the contrary, false beauty is showy, aggressive; it imposes itself with its cumbersome presence and asks no one’s permission to make conquests in our soul. In Dostoyevsky’s work, there are splendid positive figures, who show genuine beauty, genuine hope; it is we who are unable to grasp them. You just have to think of the chapters dedicated to the elder Zossima in The Brothers Karamazov, and on the other hand the celebrated discussion between Ivan and Alyosha. In his rebellion, Ivan imposes his own personality, his own will. Though he tells his brother that he does not want to interfere with his vocation, he actually says he is unwilling to “surrender” him to the elder Zossima.

Dostoyevsky wrote, “My hosanna has passed through the crucible of doubt”…

He knows all the breadth of human evil, but he also knows the truth, and he doesn’t defend himself from it. This is the point–we, too, know the truth, and so does Ivan, who takes refuge behind the refusal of God in the name of the horrors and the sufferings inflicted on innocent children. And we, too, at first, would be ready to accept his affirmation that a mother cannot forgive her child’s killer–that she has not the right to, even though the child himself were to forgive him! But what do we actually produce in us and around us if we accept this apparently “human” attitude? Dostoyevsky shows us immediately afterwards through Ivan himself, who tells the story of the Great Inquisitor, an old Byzantine legend in which Our Lady, after seeing the torments of the damned, implores mercy for sinful humanity. When God replies by showing her the hands and feet of her Son pierced by the nails, asking her how His killers can be forgiven, Mary orders all the saints, the martyrs, the angels and archangels to prostrate themselves and beg for mercy for all men without distinction. Before this picture, we understand that by accepting Ivan’s logic and refusing forgiveness, mankind would lose every chance of being forgiven, loved and redeemed. The mother of the Crucified not only forgives her Son’s killers, but becomes their mother, their protector and hope, despite all the evil committed, revealing in this way what is real, genuine beauty that corresponds to the human heart.

The century of Dostoyevsky was a century of utopianism, of a hope placed in human hands. Today, mankind is more tired and superficial, and often seems to take refuge in consolatory hopes, in a reasonable selfishness. How can we find genuine hope?

Dostoyevsky shows us that Christianity is a great paradox, precisely from the point of view of worldly reason considered as the measure of all things. Beauty does not exist, truth does not exist, hope does not exist in a definitive way, if we lose the link with the other world, which founds and gives meaning to everything that exists in this world. We have continually to recover a logic that is not ours, but that we recognize as truer and more human and correspondent to our heart than that which we would instinctively use. It is striking how, for Dostoyevsky, reality is totally intertwined with the Gospel, and how for him the Gospel and the living presence of Christ are a continuous reference for what happens, in his personal life and in the current events he comments on as a journalist. Behind every image evoked by Dostoyevsky, we see the living, existential reality of Christ, which we have reduced instead to a purely aesthetical, affected perception. Dostoyevsky’s generation, and he himself in his youth, had traveled the path of Raskolnikov, the hero of Crime and Punishment, the paradigm of man created in the image and likeness of God who changes into the Antichrist because he wants to emulate Christ by working in the present with his own strength and refusing God, his salvation.

Is there an image that represents our epoch or its false hopes?

Think of the young Liza (in The Brothers Karamazov) who imagines herself crucifying an innocent child, and while it is dying in torment stands before him eating her favorite sweet, pineapple marmalade. The critics generally judge this scene to be monstrous and perverted, but actually it is an image of the Christian world, which, before Christ, burning with love and pain, finds nothing better to ask from Him but “pineapple marmalade,” the thousand futile and petty things in which we place our hope day after day. Here is Dostoyevsky’s greatness and “positivity.” From this abyss of evil Christ raises us through the evidence that we who have refused God are famished, thirsty souls, which no pineapple marmalade can satisfy. Nothing can satisfy man but God Himself, a God who hopes in us and is always there waiting for us.