Edward Hopper Clues to Destiny, on Canvas

Moments caught in time, film scenes, tension lacing each sequence… An Edward Hopper exhibit travels to Italy, sharing with Europe the work of an artist who painted “what is happening."Edward Hopper is one of those artists for whom it’s difficult to add any words. His paintings are like open declarations–no unclear shadows, no ambiguous points. It is superfluous to add captions to his works, because what they represent is so evident. And then, for those who know the East Coast, which Hopper almost never left (in particular the beautiful promontory of Cape Cod), it is not difficult to recognize the exact places. Even the time of day in his paintings is easy to guess.

Maybe this is why Hopper’s paintings have garnered such great popularity. They are depictions that anyone would willingly hang on the wall at home, easy to get to know. Hopper elicits unreserved fondness and identification. He’s a painter whom we could define, if the term weren’t a bit overused, as “democratic.”

Hopper is also a fully American painter, in his biography, formation, and choice of subjects. His first teacher at the New York School of Art, Robert Henri, told the hundreds of students who passed through his classroom, “We have to take our gaze off Paris and Rome and fix it on our own land.” Though Hopper was so enamored of Paris that he made the ocean crossing three times before the age of thirty (between 1907 and 1910), in the end, he, too, was convinced of his complete “American-ness.” “We’re not French,” he wrote, “and never will be, and any attempt to be such means denying our heritage and trying to impose on ourselves a personality that is only a superficial varnishing.”

Minute Details

Identifying himself as American meant freeing himself from all those formal complications roiling in European art. It meant accepting the challenge of simplicity, even at the risk of seeming ingenuous: American art was in its infancy, one dimensional, elementary. Hopper didn’t back away from this destiny, even though as a youth he’d caressed the far more fascinating, elevated, and sensational horizons of European art.

And yet, comparing Hopper’s paintings to those of other protagonists of American pride, such as Thomas Benton, Ben Shan, or Grant Wood, one easily perceives they have a different approach. While his companions considered America a refuge, albeit vast, a sphere artistically protected from the complicated challenges of European painting of those early decades of the century, Hopper perceived America as a call to his destiny.

America for him was the appointed place for a decisive rendezvous with the meaning of time and existence. It is a precise place, namable, identifiable, as mentioned before, both topographically and temporally. A real place, then. But if this is the way things stand, it means that Hopper’s works fascinate not only because of what appears in them, but because of what they strain toward. In the clarity and bareness of their content, they evoke the sense of an elsewhere. The more you look at them, investigate them, and scrutinize them, the more you have to yield to the evidence that their center doesn’t lie within the composition. It’s an external center that doesn’t appear but that is the raison d’être of those images, even though they are so expressive, so knowable in their most minute details.

Be Prepared

Hopper’s painting is cinematographic because of its latent suspense, its preparation for the following sequence, which we know is certain to be decisive. Of course, unlike in the movies, the solution doesn’t come; here, Hopper’s genius engages the observer, disturbing him from his simply passive role.

In fact, one of the characteristics of Hopper’s paintings is that they never raise the question of their meaning (he himself was irritated with those who read his paintings as a metaphor for solitude); if anything, the question is about what’s happening. When you look at them, you’re instinctively led to examine the particulars as if they were clues to a story that the painter has spread on the canvas, without obviously revealing its solution.

Let’s look, for example, at those two women on the balcony of their house, who seem to be simply enjoying the brilliant Cape Cod sun (Second Story Sunlight, 1960). Actually, there’s an unusual silence all around. They seem to be passing time in expectation of something that should happen any minute. The girl in the bathing suit, seated on the balcony railing, is looking down, where we might imagine there to be a road–it seems someone is about to arrive. Who is it? What is he bringing? The elderly woman, set further back, is trying to ease the tension of the wait with informal chatter. However, clearly the key to this picture doesn’t lie in the present, but in that imminent future that creates the tension.

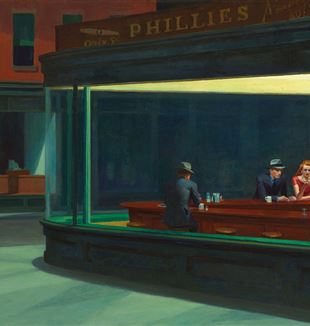

In turn, in the most famous of Hopper’s paintings, the night patrons of that bar walled by an immense window that hides nothing aren’t simply waiting for closing time (Nighthawks, 1942). There’s an action in course, only alluded to, then left suspended in mystery. They’re certainly hatching something in that empty city sunken in silence: maybe a lovers’ agreement. But certainly they are not there by chance. And we, above all and like them, are waiting for something to happen–something unconsciously awaited, something that unties the knots, that reveals destiny. A redemption of the day to day…

And in the office with the lights on late in the evening, the boss and the secretary aren’t just tidying up the last bits of business ('Office at Night', 1940). They’ve remained there to deal with private, important issues; there’s an understanding that needs no words, just a gaze. You sense that the night will be long and laborious; the imagination of the observer can set off thousands of possible scenarios. But the real work of those two seems to be to “be prepared.” Prepared for what? Once again, it’s material for the next sequence.

It Doesn’t End Here

The three paintings we’ve described are fixed images. They’re freeze frames, capably suspended in time. They seem like films on their next-to-last sequence, for the last lies entirely in the heart and mind of a director who, however, knows he can’t possess his stories. He knows that the next image is a vanishing point, something that can’t be shot. Hopper is that director: masterful in operating the camera, perfect in organizing the set, abunequalednequalled in the use of lighting. With this ability, he can elicit intense expectation in scenes of apparent stasis. He’s a director who never writes the endings; at best, he can allude to them. Thus, the viewers know with certainty that the story doesn’t end there, and have to come to grips with that point toward which everything visibly strains.