The Wound of Beauty

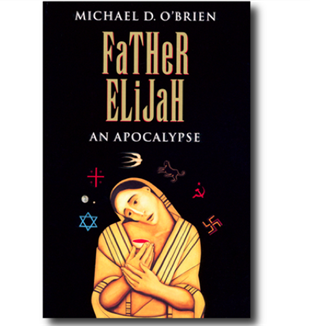

The Canadian writer and painter, Michael D. O’Brien speaks to Traces of his relationship with beauty, of his wonder before the Mystery of reality, of freedom, of being both sons and beggars, and of love as knowledge.“This book will break your heart, and will show you why your heart needed to be broken.” Thus a reviewer of one of the stories by Michael O’Brien, the Canadian painter and writer (author of Father Elijah: The Apocalypse, among other works). His stories tell of men and women, often humiliated and injured, apparently of little importance, but whose “little” choices, whose journey toward love and truth, prove decisive for the destiny of the world, capable of leading others to love and freedom. O’Brien has been compared to writers like Flannery O’Connor, Graham Greene, and C. S. Lewis.

During the last Spiritual Exercises, Fr. Carrón continually reminded us of our original dependence on the Mystery of God. He told us that every man is a “direct, exclusive relationship with God, and the reverberation of this is our being poor beggars.” You, on more than one occasion, have reasserted that the most terrible wound inflicted on modern man is the loss of spiritual fatherhood. What does it mean to you to discover yourself as God’s son, a poor beggar of the Mystery of God?

This seeming contradiction, that we are both sons and beggars, is not in fact a contradiction. We are beloved in the eyes of God our Father, yet the image and likeness of God within us has been damaged. We are like beggars because we are profoundly poor in our being, our intellect darkened and our will weakened by the fall of man, and we remain capable of much evil. Yet our Father loves the image of the Son within us. He sees who we truly are in Him, how we were intended to be “from the beginning,” as Sacred Scripture says. Like the Prodigal Son who returns begging to his father, we do not claim any rights for ourselves. We open our hands and hearts in trust. And He pours forth what we need–most importantly, He gives us our identity as true sons. If we are “beggars,” it is as beloved beggars. Christ has lived with us and died with us in our poverty. And He wants to take us with Him back into the Palace as full inheritors of the Kingdom.

In my own life, many powerful graces have come when I pray in a condition of weakness, without any merit of my own, when I have nothing to offer the Lord except my little bit of trust in His promises. The older and older I become, the more I realize that we must grow younger and younger in the heart, and become as little children. In this regard, I must say that poverty is my only riches. And, strangely, it has been the source of much joy. When we are this poor, then we can allow our Father to give to us.

What happens to a man when he forgets or rejects this relationship?

Unless we mature in Christ (that is, until we become like little children), we are like troubled adolescents who want to be “independent,” who reject authority and restraints of any kind, thinking this makes us more “free.” In the worst case, it becomes a way of life that leads to ever-deeper blindness and grave malformations of one’s perceptions and one’s acts. The modern person without faith is, in a sense, adrift in a cosmos without orientation. He lives in a flattened world, though it is filled with powerful stimuli and much noise.

He does not know himself, and thus he seeks to fill his hunger for identity through the immediacy of the physical senses, or through power and manipulative control over others, or the drug of social-revolutionary ideology, or false “spiritualities” to fill the void that opens within himself, or by making idols of various things. As a result, regardless of how relentlessly he seeks love, if he does not develop the genuine responsibility of love, he becomes less able to authentically offer the gift of himself as a unique person. I know this dynamic very well, since this was my life during part of my youth. I was extremely blind–and worse, for I did not know I was blind and believed that my blindness was superior vision.

Very often, the Holy Father has repeated that the encounter with Christ is the encounter with Supreme Beauty, and that beauty opens a wound in man’s heart. Man is wounded by the beauty of Christ. Can you help us–as an artist–to understand more how a “piercing beauty” can help man’s journey?

The beauty in creation is an expression of the beauty of the One who created it. It is language, incarnate words from our Father in Heaven, given and redeemed through the Son, by the sweet fire of the Holy Spirit. Much awareness of this begins in us before we know its true meaning, for God has written it into our nature. If there are things in material creation, or in the arts, or in human experience that bring us to our knees in reverence and awe, how much more will be our encounter with the hidden face of God in the light of eternity!

Plato says that philosophy is born of “wonder,” which is a reverent awe before a mystery–a mystery which somehow speaks to our souls, telling us that this, here, now, is a moment of discovery, an unveiling in supra-rational modes of the true meaning of my life. Poetry also is born of wonder. Love, too, is born of wonder before the miraculous being of the beloved. Through such encounters, we come to realize that we are subsumed in the Great Story, the great and mysterious work of art that is a living masterpiece-in-process, not a dead cultural artifact, still less a mechanism. The arts are, in fact, languages of the human spirit. At their best, they are co-creations, the human spirit and the Holy Spirit working together to bring new beauty into the world.

But within this wonder there is the parallel awareness that we have not yet arrived at the full restoration of all things in Christ, that the world around us and our own interior life still suffer the terrible damage caused by the fall of man. When we grow quiet inside, in a state of attention, listening deeply and silently before a work of art or another human soul or a phenomenon of the natural world (the sea diatom, the song of the lark, the masterful symmetry of the pinecone, or the immensity of stellar constellations), we can feel simultaneous joy and sorrow. We may feel an absence, such as the pain a lover feels when separated from the beloved. We feel a yearning, like the profound emotions we experience when we are stirred by certain kinds of music. Why do people sometimes weep during symphonies, and cannot explain why they are weeping? Why do some people weep at certain passages in Dante’s Divine Comedy and cannot explain it? These are healing, consoling tears, yet they also contain sadness. But why the sadness? It is because they have heard in the depths of their souls an incarnated living “Word,” and in this way have encountered the Spirit who speaks through the artist. They are in some way liberated by the work of art, and they sense this “wounding” as a sweet one. Through it they come to know a little better who we are, our eternal value, the whole truth about man–his glory and his failure. And so there is the simultaneous joy of discovery and also a sorrow over how blind we have been and how far we have yet to go.

In Father Elijah, the main character finds the ultimate relief and help upon discovering himself always loved, in the sacrifice of someone else: his parents, Pawel, Fr. Matteo, Anna, the Holy Father... through all those lovable faces, he found himself reached by Christ Himself, who attracted them “into the dynamic of His self-donation” (cf. Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Charitas Est): the Holy Sacrament, the pinnacle of that dynamic. Is it this that is forgotten and rejected by the high priests and intellectuals who, in your novel, succumb to the lies of evil power? Do you agree with Fr. Giussani, who said that the grave fault of some in the Church was and still is “being ashamed of Christ”?

Yes, absolutely. Love shows us who we are as persons. But who is perfect love? It is Jesus in the Holy Trinity, on the Cross, in the Holy Eucharist. In human relationships, would we be ashamed of the person we are in love with? Would we be afraid of introducing him or her to others? Would we be ashamed of our spouses and children? Would we hide them away and not mention them because it might make difficulties or cause tension with people who do not understand what marriage and family is? If so, then we really do not know our beloveds, and we certainly do not love them. So why would we do this to our divine Beloved?

This failure is usually rationalized by the argument of “strategic considerations.” I do not mean prudence or wisdom; I mean rather the basic human tendency to rely on our own skills and knowledge to bring about a perceived good or to avoid difficulties. Many people of good will in our times succumb to a false interpretation of the “lesser evil” argument. It is a very dangerous thing to become a “strategist for Christ.” Too easily, human thinking replaces the Mind of Christ. Too easily, a subconscious neo-gnosticism can infect the discernment process, and then the exercise of spiritual gifts weakens and grows dormant. Too easily do we lose sight of Our Lord’s call to be “signs of contradiction,” if I may use the prophetic words of Simeon in the second chapter of St. Luke’s Gospel. Is this not the test that comes to each of us, the great and the small alike? Upon such tests a person risks his whole identity, often without realizing it. In these choices, we come closer to Jesus or move farther away from Him. In a word, it is the mystery of the Cross.

You are a great admirer of Tolkien’s and Lewis’s works. At the same time, you have more and more times warned about the peril of “a corruption of the imagination” at work in many recent fantasy novels for young readers. What do you think is the main difference between a great and valid work of imagination and a false one?

This question requires a book-length answer. But a few simple concepts may be helpful to an understanding of the matter: Man is a being of symbols, and his symbols play a crucial role in the architecture of his consciousness, and in the formation of his moral conscience. Conscience influences our perceptions, and hence our actions. If we lose symbolism, we lose our way of knowing things. If we destroy symbols, we destroy concepts. There is another danger: If we corrupt symbols, concepts are corrupted, and then we lose the ability to understand things as they are, making us vulnerable to malformation of our perceptions and our actions. For example, many contemporary fantasy books employ the symbology of witchcraft and sorcery as metaphors or plot dynamics, presenting them to young readers as morally neutral and sometimes as positive goods. Clearly, this is corruption of the moral order of the cosmos. Tolkien wisely pointed out in his essay on fantasy that no matter how wildly the author departs from the physical order of the universe, he must take care to be faithful to the moral order of the real universe.

Healthy fantasy–the “baptized imagination” or the “incarnational imagination”–draws us to a sense of wonder, and wonder in turn moves man’s interior awareness to a sense of the transcendent, the Wonder in which we live and move and have our being. By contrast, corrupt fantasy moves the reader into a world of visceral stimuli, thrills, the ego, the false self. It may weave a few “values” and traditional aspects of fantasy into its mesh, but it will also exhibit internal contradictions. At the very least this is moral confusion for the young reader; it can also generate powerful negative role models.