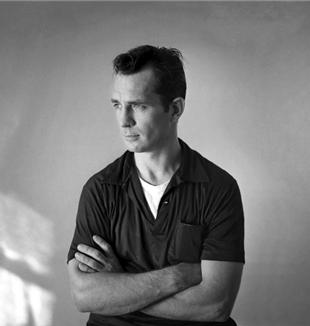

Memory Babe

The author of "On the Road," a cult book for a generation of rebels. A dramatic life that ended in drugs and alcohol. But his pitiless analysis of American society was never satisfied with a degraded condition.His real name was Jean Louis Lebris de Kerouac, but with a “calling card” like that, which could easily descend from King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table, it would have been unlikely for the author of On the Road to have become one of the major protagonists of the Beat Generation. This was Jack Kerouac, who was born in 1922 and who died in 1969 after 47 years of a life that became an icon, very often mistakenly, skillfully manipulated by publishers who often turned up their noses at Kerouac’s writings and refused to publish them.

The great risk in talking about Kerouac is that of confusing the person with the writer; a dramatic life that ended in alcoholism laced with drugs with his literary production. Kerouac himself, two years before he died, trying to break free of the “cage” in which he had been put after his success, but still faced with an obtuse ostracism, had said in an interview to the Paris Review, “I am so busy interviewing myself in my novels and I have been so busy writing these self-interviews, that I don’t see why I have had to put up every year of the last ten years with repeating and repeating to whoever interviewed me what I have already explained in the books themselves… It doesn’t make sense.”

The categories in which Kerouac has been confined demonstrate yet once again the publishing “war machine’s” cultural lack of substance in the mass communications circuits of today’s world. Kerouac’s sensitivity, which was his condemnation, and his incredible memory of every passage of a lived life slide into the banalization of “another Catholic drinker,” as was said of F. Scott Fitzgerald in his time. He might also fall into the category of the “accursed writer,” so trendy once he is dead, who can be passed off, according to circumstances and convenience, as a Seventies hippy or an Eighties and Nineties rapper, or whatever fashion has to be “gift-wrapped,” as book and matching T-shirt, for the Fifth Avenue bookstores. How different was the Jack Kerouac remembered by the first girl who loved him, named Mary Carney, rooted in the serene life of a New England town: “He was a good, sweet boy, and the people of Lowell did not understand him. They never understood him. No one ever reads here. They haven’t even given him a plaque. Jack was so sensitive; all he wanted was a house and a job on the railroad. Jack always told me everything. But no one would understand, so I won’t say anything more. I decided a long time ago that I would not say anything more, and I’m keeping my word. Anyway, no one listens to you.” One could say that this does not happen only in Lowell, Massachusetts.

A Grotesque Atmosphere

Kerouac was a simple, straightforward boy, who knew early grief in the death of his nine-year-old brother Gerard. But the family into which Jack was born and grew up seemed to be a world of complications and pain, with a French-speaking mother, Gabrielle (the so-often evoked Mémère), who wanted a famous son more for her sake than for his. It must have seemed strange and bizarre (if not grotesque) to Jack, when he was a student at the famous Horace Mann School in New York, to have flunked French because his mother spoke a patois that had very little in common with the language of Balzac and Proust. It was also strange and bizarre for Kerouac, who grew up with his sister Nin immersed in a love of culture (“Now we’re grown up, let’s read books”), to enter Columbia University–a temple of New York culture–because of his athletic prowess. He was a football “pick” of coach Lou Little, a celebrity who had Americanized his Italian name, Luigi Piccolo.

But this grotesque atmosphere, an overall one, not just family and scholastic, is precisely what produced the existential tragedy of Jack Kerouac. The boy who was good at football, who threw himself into his reading and who, wherever he was, wrote and rewrote his impressions and memories, spent–and sometimes wasted–his sensitivity, ground up by the American society he observed, mixing it in with every memory.

He recounts in 1951, “I remember a reception at the Ritz Yale Club where I went with a boy who was wearing a leather jacket, I was wearing one too, and there were hundreds of boys wearing leather jackets instead of hot-shot millionaire’s top hats, and everyone was smoking pot, painfully commemorating a new decade in one wild crowd.”

To get away from this wild crowd, the new WASP [White Anglo-Saxon Protestant] conformity of post-war America, the revised new edition of Calvinist-capitalist society in which the notion of work time was brutally given a monetary value, in the face of that moralistic and hypocritical society, Kerouac chose to go “on the road,” to live the precarious existence that Jack London had already described in The Road. The sensitivity of a simple boy, his love of culture, and the defense of belonging to a lower middle class American Catholic family all led Kerouac to live his precariousness all the way, between rivers of alcohol, unbridled sensuality, and a sporadic but continuing use of drugs. He wrote The Subterraneans in 72 hours while he was high on benzedrine. For publishing reasons, he was forced to change the name of the city where it was set, and New York became San Francisco. Living his own sensitive precariousness brought him into contact with the great open spaces of America, traveling from one end of the country to another, in an escape, a flight without meaning in order to remember his life better, the characters of his life, to the point of obsession with memory, so that he was taken for a “memory babe,” a child with a prodigious memory, as everybody called him.

A New Expressiveness

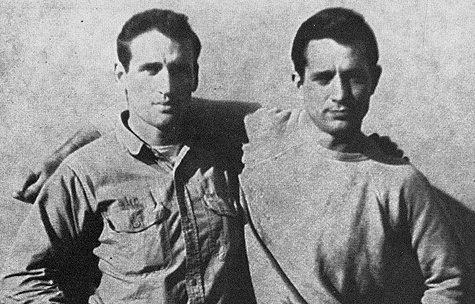

This type of existential rebellion, lived in his own flesh, contains the passion of a revolt that is also literary. Jack Kerouac, in the cult book that became emblematic of a generation, reaches almost a paroxysm of spoken language translated into writing. Kerouac is practically the last frontier of this type of writing, whose roots and traditions reach all the way back to Mark Twain, Jack London, and Ernest Hemingway. On the Road is a writing of rapid-fire, first-person speech. The trip has no precise goal, in the final analysis like that of Melville’s Captain Ahab or Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. The trip is only a movement through space, which produces inner movements, where people come together, word games are invented, friends are seen again, and memories arise. The way Kerouac, and all the Beat Generation, wrote books provoked a derisive reaction from a classical narrator like Truman Capote, who said, “None of them knows how to write, not even Jack Kerouac. That is not writing, but typing.” But in this case, the brilliant author of In Cold Blood was wrong. The speed with which Kerouac wrote seemed like that of a skilled typist, but On the Road was meditated, thought out, and written and rewritten several times, with an intense search for meaning. And the style contained the core of a new expressiveness that had its correlatives in other arts, like film. For example, one of the protagonists of On the Road, Dean Moriarty (Kerouac’s friend Neal Cassady), is a prototype of what came to be called a hipster, a character who abandoned every false security to live every instant of his life spasmodically, consuming it in a flame of pure energy. Moriarty-Cassady could be compared to Marlon Brando in Wild One or James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. Moriarty lives a condition of life, an expressiveness that is bodily, ironically, paradoxically, flauntingly opposed as a melancholically lived challenge to the WASP prototype of the new American society. Kerouac gave it its best literary interpretation.

The Return Home

But Kerouac’s impassioned remembering, his pitiless analysis of American society, is never satisfaction with a degraded condition. At a certain point, for a period of his life, he became a Buddhist (between a drinking binge or an episode of sex), but Kerouac always said, “I am a strange solitary crazy mystical Catholic.” His obsessive memory returned again and again to the places of his childhood, the roots of his existence. The flight, the escape of On the Road is never one-way. The great open spaces of America, its unreal sunsets and dawns, the syncopated beat of jazz that travels with you on your way, the pool halls, the women, and the chance encounters remain in Kerouac a parenthesis in his lived precariousness. He wrote in a heart-rending moment, “October is the sweetest month. In October everyone goes home.” And he, the rebel, advertised as a forerunner of the hippies or of a certain kind of left, always wanted to go home. Probably, Kerouac had very little to do with the counter-culture of the American left in its various forms. His love for America was boundless, even bringing discussions to shouting levels over it. His attitudes and some of his judgments seem more of the right than the left. The paradoxical world of his friends called for an implacable irony. Allen Ginsberg, a great friend of Jack’s, the son of an unbending Communist, almost provoked a diplomatic incident when he was invited to Cuba by the new Castro regime. In his mocking way he said that Che “was cute” and that Fidel’s brother Raoul “was maybe gay.” He was immediately invited to return to the States so contested by the left.

On October 20, 1969, by his mother’s side, Kerouac was taken ill. He died the next day of an internal hemorrhage. His funeral was held in Lowell, and Jack, by the intervention of his rebellious friends, was buried in the Catholic Edson Cemetery. He had come home. To the roots of his life.