The Pursuit of Happiness and the Art of Belonging

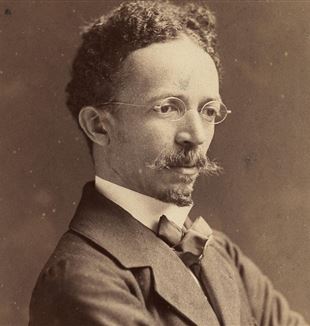

We present here the story of the great black painter Henry Tanner who lived during trying times when the question of race was dramatic in America. Nowadays, his talent is fully appreciated, and we can admire his works even at the White House.Washington, DC, 1860: Angry white snow in a bellowing wind, and stranded, street side, are Sarah Tanner and her infant son, Henry Tanner. The streetcar sign glared in big block letters: NO NEGROES ALLOWED. But the cold and a love for Henry conspire to move Sarah Tanner toward risk. She pulls the veil down over her face, concealing, she hopes, her dark African features. She mounts the streetcar and takes a seat for the ride home to Alexandria. Minutes pass but soon there are stares, curiosity, then surprised realization, anger, harsh words, and Sarah and her baby are forced out into the blinding white driving snowstorm.

Henry was 13, walking through Philadelphia’s Fairmont Park with his father, when he spied a landscape artist hard at work painting an immense elm. And there it was, unexpected, like a first kiss–and Henry was suddenly, immediately, aware that something had changed. He returned to the park the following day to the artist’s exact spot, excited and untutored but sure of his vocation, the canvas propped precariously between his bony knees, paint flinging everywhere–on the canvas, on the grass, on himself–and he was happy, supremely so. “My parents gave me all the encouragement their limited means would allow. By encouragement, I mean not only moral support, but a home.”

The question of race–which is to say of home, of belonging–was ever present for Henry, and during the early years of seeking instruction it was an especially problematic one. “With whom should I study?” he asked. The question was not, “Will the desired teacher have a boy who knows nothing and has little money?” The question was, “Will he have me?” Or, “Will he keep me after he finds out who I am?” This concern over belonging, over being excluded because of his race, pressed itself down upon Henry his entire life, and he developed a deep antipathy toward any sort of racial classification.

Philadelphia summers are sweltering, and so the Tanner family, like many black families in the area, sought the cooling breezes of the Atlantic seacoast, vacationing in Atlantic City. Waves and salt spray and sailboats were therapeutic for Henry’s always-delicate health, and offered him many subjects for painting. A few of his sketches and paintings caught the eye of another Henry, Henry Price, a summer resident of Atlantic City who was also a Philadelphia artist with his own studio. Price offered Tanner a one-year apprenticeship, which was eagerly accepted, and Tanner began in earnest to learn the craft of art. Price eventually terminated their relationship in a huff, once visitors to the studio began expressing greater interest in the student’s work than the teacher’s work.

Henry’s father, Benjamin, a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was pleased with his son’s enthusiasm for art, but was a practical man and could not see it as a true and viable profession, especially given the racism so entrenched in American society. He encouraged his son to take a position in a flour mill, which Henry did, obediently if unenthusiastically, but the work quickly proved too draining on his strength.

In Search of Something

His health eventually restored, Tanner enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts on December 4, 1879, becoming the first full-time black student in the school’s history. Joseph Pennell, a fellow student, later gave an account of Tanner’s acceptance into the school: “There was every kind of man and boy, from sixty to twenty, in that class, except black men, and one day the Chairman of the School Committee appeared [with] a solemn announcement that he was coming… And he said something like this: ‘A drawing has been sent in and passed. The person who made it…is a colored man….We decided that we had no objection.’” We learn from Pennell that the racial animosity of certain students–inflamed, it seems, by Tanner’s obvious talent and ambition–was heard by Henry nonetheless: “He worked at night in the Antique, and… he drew very well. I do not think he stopped long in the Antique–the faintest glimmer of any artistic sense in a student, and he was run into the Life [class by Professor Thomas Eakins]. He was quiet and modest. Little by little, however, we were conscious of a change.… He seemed to want things; we seemed in the way, and the feeling grew. One night his easel was carried out into the middle of Broad Street and, though not painfully crucified, he was firmly tied to it and left there.”

Tanner stayed at the Academy for two years, and spent the next seven trying to establish himself as a professional artist in Philadelphia. He struggled financially. Unsatisfied, he packed up and headed south, living and working and painting in Florida, Georgia, and the mountains of North Carolina. His travels at this time betray a restlessness, a searching out, a haphazard grabbing at something he couldn’t see but desperately wanted. He crisscrossed the South, finally resting briefly in Atlanta where he taught art at Clark University. One of the university’s trustees, Bishop Joseph Hartzell, became, along with his wife, early and lifelong champions of Tanner’s art, and the devoutly Methodist couple arranged to finance a trip abroad for Henry. He’d long wanted to study in Rome, to see the masterworks of the centuries, and to enjoy the relaxed racial attitudes of Europe. There was also a sense that art simply wasn’t taken seriously in America at the time, and that any artist with ambition would of necessity sail for Europe–which Henry Tanner finally did in 1891, bound for Rome via London and Paris.

Paris: The City of Light

London may have been impressive to Tanner, but Paris was something else altogether: the sound of a key turning in a lock with a satisfying click. “Strange that after having been in Paris a week, I should find conditions so to my liking that I completely forgot when I left New York I had made my plans to study in Rome and was really on my way there when I arrived in Paris.” What Tanner found so exhilarating was the freedom to be himself, to pursue the happiness and sense of belonging that had so often been denied him in America.

Tanner enrolled in the Academy Julian in Paris and immediately distinguished himself among the students. Between 1891 and 1895, he completed a series of paintings that offer an insight into his developing philosophical and religious outlook. Having devoted most of his early canvases to landscapes, he now focused on the shared humanity of the world’s peoples. The Banjo Lesson and The Bagpipe Lesson, two of his more famous paintings from this time, are remarkable for what they intimate about the human condition. Henry’s father had impressed upon his son at an early age the importance of memory, choosing as Henry’s middle name Ossawa, in honor of the Kansas town where abolitionist John Brown defeated pro-slavery agitators. 'The Banjo Lesson', a black genre painting, is set in a rustic cabin and shows a father or grandfather teaching a small boy how to pluck the strings of a banjo, an instrument with African roots; The Bagpipe Lesson, meanwhile, is a similar composition but is set in a blossoming orchard in the Normandy region of France. Tanner illustrates a universal human activity–the transmission of culture, of roots, of a sense of community and home–and demonstrates that the beauty inherent in this activity is not heightened or lessened by the lushness or sparseness of the settings in which it takes place.

The Turning Point

Daniel in the Lion’s Den marked a major turning point in the life of American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner. It was the first painting on a religious theme he had exhibited at the Paris Salon, and its recognition by the Salon juries in 1896 seemed to launch him in a new artistic direction. The painting’s importance lies not in its composition but rather in its theme. Tanner never explained why he chose this particular Old Testament story, but its importance to him is evidenced by the number of times he painted it: at least three–in 1895, in 1900, and yet again in 1914. The name Daniel means “God judges, “ and Tanner, a deeply religious man whose quiet faith had been passed on to him by his father, and whose struggle against the prevailing racism of post-Reconstruction America had necessitated his leaving the country for Europe in 1891, no doubt saw something of himself in the figure of the prophet: calm, quiet assurance in the protective benevolence of God.

The year 1897 saw Tanner enjoying the success of the previous year’s 'Daniel in the Lion’s Den' and moving even further into an exploration of culture and place. It also saw his introduction to a white opera singer from San Francisco, Jessie Macauley Olssen. Their attraction to each other was immediate and profound, and after Tanner left Paris for a tour of the Holy Land it took only a three-word telegram from Jessie to bring him back: it read, simply, Come to me. They wed not long after.

Tanner’s 'The Resurrection of Lazarus' shocked the art world in 1897 by winning a medal from, and being purchased by, the French government, which eventually hung the painting at the Louvre. The June 13, 1897, edition of the Boston Herald had this to say of the painting: “One of the serious successes of this year’s Salon of the Champs Élysées was a comparatively small canvas representing a biblical scene, the ‘Resurrection of Lazarus’ and signed H.O. Tanner. The signature brought to memory some four or five paintings exhibited over the past few years, each of which was excellent in point of color, tone and style, and possessing as well that magical, sympathetic quality that is akin to the sacred word of genius.”

Thus began the most productive period in Tanner’s life. He wed Jessie and they purchased a home near Etaples, Pas-de-Calais, and had a son, Jesse. Henry’s family served as inspiration, and it is striking how often the theme of family appears in his paintings during this time. 'Mary', 'The Flight to Egypt', 'Christ Among the Doctors' (all 1900); 'Mary Pondered All These Things in Her Heart' (1908) and 'Mary Visits Elizabeth and The Holy Family' (both 1910); and 'Christ Learning to Read' (1911) all use familiar New Testament figures to explode and illuminate the domestic life that Tanner was now experiencing firsthand. It was a time of intense joy for him, the consummation of his years of longing and searching and hoping, and it would be, sadly, short-lived.

The Last Years

The bloody rupture of World War I tore dangerously close to the Tanner home in Etaples, and the family was forced to evacuate and flee for England. This would mark yet another turning point in Tanner’s life. While his final years would see the bestowing of many honors–he was elected to the National Academy of Design in America and made an honorary chevalier of the Order of the Legion of Honor in France–they also saw the loss of Henry’s mother, father, and beloved wife. Modernism became fashionable and consequently the realism of Tanner’s art became passé. His home, however, became a pilgrimage site for young African American artists who sought his advice and inspiration, and recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in the man and his art. Henry Ossawa Tanner died in Paris, alone, in 1937.

Washington, DC, 1996: The East Room of the White House thrumming with bodies and talk and a special reception unveiling the most recent addition to the White House permanent art collection–Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, by Henry Ossawa Tanner, son of Sarah, his mother who had escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad to the North. “Talent,” the First Lady notes, “always has the power to transcend prejudice.” Nods and warm agreement from the assembled guests, and Henry Ossawa Tanner takes his place in the nation’s home with other acknowledged masters proudly displayed there, a brother to John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt, and Winslow Homer.