Like in a Movie

A review of more than 150 years of film history reflecting on attempts to answer Jesus’ question to His Apostles: “Who do you say I am?” From the origin of film through Hollywood’s post-war spectacular epic years.“His greatest merit… It was the only film of its type that did not contain the figure of Jesus. There was not one trace of Christianity in Spartacus. Faith was there, but not Christianity. If Kirk Douglas had to be rewarded for his courage, it would be for having made a movie like that without Jesus… but with Kubrick!”

With these words, Sir Peter Ustinov recalled the importance of the great Stanley Kubrick in the film that reconstructed his biography (Stanley Kubrick, a Life in Pictures, Jan Harlan, USA, 2001). But his comment, referring to the spectacular epic Spartacus directed by Kubrick in 1960, produced by and starring Kirk Douglas, ironically reveals another fact: the figure of Christ appeared so frequently in movies between the 1950s and 1960s, especially in the historical films produced by Hollywood, that He could be found almost everywhere, even if only making an illustrious “cameo appearance” in the cases when His life on earth was not a direct theme of the movie.

The reason for this constant presence is that Jesus, the Son of God made Man, precisely because of His life in the flesh, could also be represented in any form of the figurative arts. Let’s attempt here to review, albeit summarily, more than 100 years of film history to see how directors have tried to respond through images to the crucial question Jesus Himself asked His Apostles 2,000 years ago, but one that still today affects anyone who does not want to leave unanswered the question of the identity of the only Man in history who said He was God: “Who do you say I am?”

In the earliest days of motion pictures, the Bible

Our review of more than 100 years of film history takes us back to the origins of the seventh art, and not without an adequate motive; for already at its origins, roughly from 1895 to 1910, movies offer us, surprisingly enough, a good number of films focusing primarily on the subject of Christ’s Passion. In 1895, the year of the first public projection of a film, a movie was made called Passion Léar, after the name of its creator, the French director Kirchner, known as Léar, while just two years later, in 1897, Passion Lumière (Vues représentantes la vie et la Passion de Jésus Christ) came out, made by Bréteau and Hâtot for the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, the inventors themselves of cinema. Also in 1897, The Passion Play was filmed in the United States by Vincent and Paley. In 1899, Christ marchant sur les eaux by the French director Georges Méliès showed viewers the miracle of Jesus walking on the water, an illusion created using one of the earliest and simplest special effects known to film-making, superimposing one image over the other. Italy was not to be left behind, and in 1900 Passione di Gesù was screened, a work by Luigi Topi and Ezio Cristofari. However, the most complete and mature achievement among these early films is the work of another Frenchman, Ferdinand Zecca, who made between 1902 and 1907 what is known as the Passion Pathé, named for the glorious pioneering movie studio.

All these works have in common a fairly naive illustration of the Gospel events; they are simply documentary films of religious plays put on during folk festivals and holidays, like the famous Oberammergau Passion Play in southern Bavaria. Performed by amateur actors, wrapped in cloaks similar to Roman and Hebrew tunics and reciting in front of flat, painted backdrops that reproduce the sacred places of Palestine, these short films outline the history of salvation, but without going into a deeper interpretation of the Mystery evoked in these gestures. This was above all because of their brief duration, due to the short length of a reel of film, which limited them to a maximum of ten minutes projection time.

But the real reason for so much interest in this subject, 2,000 years old but still timely, is, as recent studies have shown, intrinsically linked to the possibility of articulating the narrative in a series of tableaux vivants that offer living pictures of the most important events of the life of Jesus. For if the early films made by the Lumière brothers are nothing more than short takes in which one event or one comic episode completely runs its course, thus making every shot a film in itself, the only way to overcome this physical limitation was to juxtapose two different shots recounting two different episodes, by means of the operation today generally called “editing.” However, those early viewers had no reason to suppose that this juxtaposition of different frames meant creating a connection of meaning between the images, as today happens completely automatically, for example, when we see a man looking at something and then immediately afterwards see the object at which he is looking. For our ancestors, it was simply a case of two films shown one after the other, but totally disjointed and independent from each other.

The events of the life of Christ, on the other hand, with their universally known sequence, even to those who only grew up in a Christian environment, permit the viewer with no knowledge of cinematic syntax not to get lost in the passage from one shot to the next, thus going beyond the simple “view” lasting a few seconds and contained in one sole take. Just as the stained glass windows of medieval cathedrals, by virtue of being made up of images, had succeeded in unfolding the Bible to those who did not know how to read–the Biblia pauperum, “the poor man’s Bible”–so does the order of events in the life of Christ enable viewers to go beyond the individual frames, because it is clear to everyone that after the Last Supper must come the prayer in the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus’ arrest, trial in front of Pilate, flagellation, walk to Calvary, crucifixion, death, and resurrection. At the origin of moving pictures, right in the very years of their birth, the Bible and its stories thus not only exercised, more or less unconsciously, an educational function on the masses of people who gathered every day in front of the movie theater screens, but were also an irreplaceable aid in the development of linear narrative, something that for us today has become completely ordinary and taken for granted, but at the time had to be invented out of nothingness.

After these early attempts to articulate the narrative had run their course, brought to culmination and codified by the American film-maker DW Griffith, the figure of Jesus was initially adopted as a symbol of peace in films protesting World War I. In Intolerance, by Griffith (USA, 1916), the Passion of Jesus is one of the four stories about intolerance in the history of the world that make up the film; in Civilization (USA, 1916) by Thomas H Ince, Jesus even intervenes to save the life of a soldier who has ended up in hell during the war. But the story of the life of Jesus could not help being adopted by the great season of epic spectacles set in Rome that made the fortune of Italian film in the second decade of the twentieth century.

Christus, by Count Giulio Cesare Antamoro (1916), is an example of this typically Italian study of visible space. Still uncertain about its narrative and aesthetic choices, tied more to the past than looking toward the future, the film does not go into the figure of Jesus, limiting itself to offering an easily shared imaginary universe on a popular level. It focuses its research on the organization of the space of the film frame, its depth of field, and the planes on which to distribute the various events. To this end, it does not hesitate to rely on cultured citations from works by Fra Angelico for the Annunciation, Raphael for the Transfiguration, or Leonardo for the Last Supper; or on a complex and captivating play of light and shadow, due to the recent introduction of artificial lighting also for scenes shot outdoors. Above all, it utilizes the enormous stage sets of Pilate’s palace and the huge masses of people who followed Jesus to apply a given internal order to the shot, on pain of losing the possibility to manage and later to read the image itself, which until then had not had a precise center of attention, resulting in a chaotic jumble of actions, characters, and objects agitating about in front of painted backdrops totally lacking in spatial depth.

The spectacular pretext

It was the American film-maker Cecil B De Mille who exploited to its utmost the wonderful potential offered by the life of Jesus and His prodigious miracles, which lent themselves well to the special effects that were a sure source of attraction to the broader public. In The King of Kings (1927), he offered a festival of light effects, a visual display of splendors and cataclysms to entrance the view with the astonishing effects possible with movies, leaving aside, however, any aspect of verisimilitude both in the historical organization of the film and in the deeper study of the portrait of Jesus, more than ever reduced to the stereotype of innocent victim of the world’s hatred who suffers and never rebels.

De Mille certainly does not fail to feel he is vested with an evangelizing mission toward the whole world, to be enacted using the movie camera, as he declares in the opening captions of the film: “This is the story of Jesus of Nazareth. He Himself ordered that His message be spread to all parts of the world. May this portrait play an important role in the spirit of the great commandment.” But De Mille’s purpose is only to put on a spectacular show, even at the cost of forcing historical truth just so he can achieve the result he is seeking. But this turning of Revelation into spectacle can only lead to a dead end; simplifying a problematic figure like Christ in this way means also avoiding taking a stand on the question about His identity, eluding the problem in favor of an aesthetic reduction as complacent as it is sterile. A further attempt at a more profound rendition, less banal but still in this line of a three-dimensional rendering of images, was made in 1935 by the French director Julien Duvivier, who in Golgotha, a totally forgotten film by now, made an equally recherché and superficial version of the last days of Christ’s life; it too has very little to do with a serious study of the identity of this Man.

Only after the end of World War II did movies start looking at Jesus in a more problematic way, while still not renouncing the spectacular dimension pursued up to this point. This was the result also of the emergence of a more secular, less religious culture that, however, in its own way, did not want to fail to take a stand on the identity of this Man, albeit with all the contradictions it would be capable of producing over the years.

The Gospel in Cinemascope

During the 1960s, in the brief span of just five years, Hollywood produced two colossal films on the life of Jesus, in the wake of the return to the big screen of the great spectacle offered by historical films in the attempt to counteract the irresistible rise of television and the consequent emptying of the movie theaters. These two films, albeit very close to each other in time, embody to perfection the two souls of modern cinema: on one hand the one that, after the great lesson of Italian neo-realism, tended more and more toward a recovery of and greater faithfulness to reality, and on the other, the one that acknowledged the fact that the viewer is watching a movie, that is, a work of fiction that is only a reproduction of reality, as the directors of the French Nouvelle Vague emphasized with their systematic undermining of the classical grammar of motion pictures.

Representative of the first category is Nicholas Ray’s The King of Kings, of 1961, in which, for the first time, the personal anguish and sense of social criticism of the director himself are poured into the figure of Jesus, yielding a totally unprecedented interpretation in movies until then. The film does not open with a classic sequence of the Annunciation or the Nativity, but with the arrival of Pompey the Great in Jerusalem, the profanation of the Temple and the subsequent conquest of the city by the Roman Empire. In this overtly political and “earthbound” line of interpretation, Ray proposes an essentially human Messiah, not so much the Son of God, as a possible liberator of the people of Israel from slavery to Rome. From this point of view, which is certainly partial but not at all banal, spectacle for its own sake no longer has the space to explode uncontrolled; by deliberate choice, the most sensational and marvelous miracles are not shown, like the multiplication of the loaves and fishes or Jesus walking on the water, while the visually simpler ones, such as the healing of the cripple, are poetically presented through barely suggested gestures rather than fully depicted. Jesus, played by Jeffrey Hunter, is nothing but a man, a possible military commander on whom the hopes of those who (like Judas and Barabbas) are looking for a revolution of their people against Rome are concentrated. In this sense, Judas’ betrayal no longer happens because Christ has disappointed the expectations of his heart, but is only a tactic for “forcing His hand” so that, with a knife at His throat, He will react and unleash, thanks to His abilities, the longed-for revolution against the hated Roman oppressors. For the first time, a director asks himself questions, in a problematic and not predictable way, about the identity of Christ, proposing his own version full of doubts and contradictions but that, in its own way, tries to give answers, certainly not self-evident, to the greatest problem in history.

On the other front, in 1965 George Stevens produced and directed The Greatest Story Ever Told, a huge film in which, out of all the possible ways of approaching the subject, the desire prevails to show beautiful images, to make a beautiful film, one that would leave even the most calloused viewer open-mouthed. Shot in Utah in scenery more suited to a western than typical of Palestine, the story manipulates the Gospels freely, with the sole purpose of giving the greatest aesthetic beauty and most spectacular images possible, once again harking back more to De Mille’s approach than to Ray’s efforts at interpretation. Jesus, played by Max Von Sydow, is a stick figure, always taking a hieratic stance, capable however of weeping at the death of his friend Lazarus, something never been seen before. But this and other potentially good insights are crushed and forced into the strict mold of the Hollywood spectacle, which prizes the desperate search for visual effects over any attempt to go more deeply into the subject, to the point that Jesus Himself, in the scene of the resurrection of Lazarus, is reduced to being a mere detail in a breathtaking view of the mountain into which His friend’s tomb has been dug, an image magnified even more by the splendor of Cinemascope, the new format introduced in 1952 that expands the image horizontally in order to compete with the small size of the television screen.

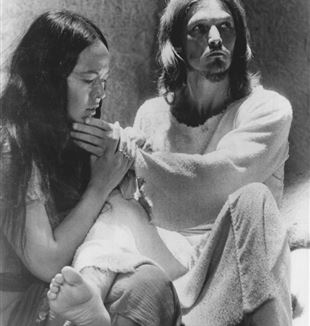

It would be precisely the problematic line indicated by Nicholas Ray that would be the wave of the future. In the years after his film, an increasingly keen interest in taking a stand on the problem of Christ began to emerge. And a first, extraordinary, unexpected answer came from Italy, from a Marxist intellectual, Pier Paolo Pasolini, who created a totally anti-spectacular image of Jesus compared to the imaginary universe consolidated by the Hollywood epics, centered on the will to get to the bottom of the problem–which he felt could not be dismissed lightly–unleashed 2,000 years earlier by a Man who claimed in front of the whole world that He was God.