A Mad Love for Life

Soldier, womanizer, wanderer, journalist, winner of the Pulitzer and Nobel Prizes for literature. The portrait of a man in search “of an adventure which can give meaning to every instant.” Fourty years after his deathWhat happened the evening of July 2, 1961, in the picturesque house in Ketchum, Idaho, in Sun Valley began with the sound of a shot, the gun falling to the ground, Papa Hemingway dead, and Mary, his wife, swearing that he was cleaning his guns and that it all happened “accidentally”–nobody has ever believed that. A life should not be recounted like this, one “lived intensely, not just passing the days,” by starting from the end. But that end was in reality the only tenacious, feared, defied, loved, hated, faced, provoked goal. Dreamed of so many times and recounted so many times. It is the end that awaits him up there on Kilimanjaro, in the midst of the snow and the leopard that shouldn’t have been there, and yet it was; the end that awaits the matador, with everything condensed into the horns that pierce and the arena that keeps getting bigger and bigger and then smaller and smaller, and then bigger, and then nothing. The end that awaits him in the middle of war and the grenades and the soldier who prays and prays to God and cries and cries and calls out for his mother, and when it’s all over goes to the tavern and gets venereal disease. The end that awaits the fencing champion with a mutilated hand, the most handsome and dignified officer in the Italian army who has nothing left of glory and splendor and only is a burst of irritation betrays his immense grief over his wife’s death. The end that awaits the sweet, lovely nurse who is in love and pregnant and escapes to Switzerland to die in childbirth, with the American soldier who volunteered for the Italian front to drive a Red Cross ambulance and see death first-hand in war and to watch the woman he loves die. The end that awaits everyone, and him too, this writer who loved life madly. The end that awaited his father, a suicide too, his father the doctor to Indians who would take his little son Ernest into the land of the great lakes, to the tribal reservations, and where he returned as a young man and fell in love with girls whose skin was darker and eyes were larger and slightly slanted, and drank cheap whisky and slept in the woods. The end that awaits the boxer who was once great and now is stupefied by the Parkinson’s disease that fogs up his brain and sleeps in train cars along the tracks and shares his beans with the boy and the black man who stayed his friend, and breaks his eggs into the sizzling lard in the frying pan at the fall of evening. Everything is worth living and recounting. And Hemingway went to look for it, this everything and the noise and silence. He found these all immediately, when at age 19 he was a reporter for the Kansas City Star, the newspaper where the page editors would shout that they wanted a line and a news item, a word and a fact, cut the adjectives, hold the comments, just who, what, when, where, and spare, lean verbs and concise dialogue.

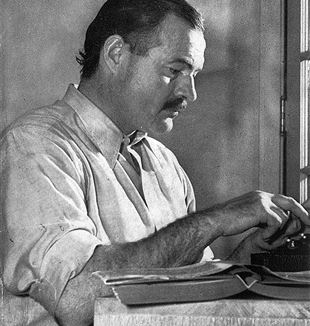

Hero and journalist

There was always something or someone worth telling about wherever he went. In war, in the first world war on the Italian front where he was a volunteer, in his homeland, in the sleepless nights that would torment him all his life, in the bottom of the bottles that he drained incessantly, but cleanly, not letting the liquid overflow or splash out of the glass, because dignity resides in a clean, well-lighted place, where you can discover nothingness and go away without letting grief break your back. There were two things he was able to do like no one else in his generation: the hero and the journalist. At the age of 20 in Italy, at the front, driving a Red Cross ambulance because poor vision kept him out of the combat troops, and so he went to the front line on a bicycle, allegedly to take medicine and food to the soldiers, but in reality to see up close the death he had to tell about, and he discovered that soldiers die a nasty death when grenades explode close to them, and machine gun fire hit him too and he kept helping the wounded with the shrapnel in his body. He was decorated twice and sent to the hospital and he kept on writing, driving the censors crazy and also driving the nurse Agnes Von Kurovwskj crazy, in the nice American hospital in the center of Milan, on Via Spadari, where he would walk in the evening and see the silver foxes displayed in the shop windows where they sold game, their beautiful tails sprinkled with snow. And he would hear the workers in the Communist neighborhood insulting the decorated officers. Agnes loved him and didn’t want to marry him. His return to his homeland was a nightmare. At home, in the beautiful house of his rich Protestant family, in Oak Park, Illinois, near Lake Michigan, he couldn’t stand it. He hunted, wrote, wrote, and drank. Then he set off again with his wife Adley Richardson. He was 21 years old and already famous.

Travels

He was capable only of living extraordinary adventures. He traveled. Paris (the Paris of the American Lost Generation, where F. Scott Fitzgerald would meet with Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein). The Switzerland of high white mountains. The Spain of white houses where you could drink strong red wine and chat with toreros after the bullfight. Greece and Turkey at war. Italy, Milan, and the San Siro evenings in the city streets when the jockeys raced to loose weight and you could hear swapped information about the horses. He lived everything, met everything, recounted everything. He was the best-loved, most extraordinary and sought-after, best-paid journalist of his time. With his second wife Pauline Pfeiffer he built a big house in Key West, Florida.

Very soon he became the writer that a generation could not do without, while war was drawing near, the war in Spain and the World War II. He went to the battlefield as a reporter and ended up fighting. He heard the bell toll for the republicans in Madrid, and understood and knew that the bell would toll for him too, sooner or later. He divorced Pauline and married the journalist Martha Gellhorn. He bought a house in Cuba, near Havana. He went with his wife to see the war between China and Japan first-hand, and when war broke out against America he came home to patrol the Florida waters in his fishing boat to try to sight Japanese submarines. And offshore he would see the flying fish cross each other in the waves and maybe he was already seeing an old man in his boat catching a big fish, the biggest, after 83 days of bad luck, and two days and two nights of struggling with the giant which would be eaten by sharks while he was dragging it back to Cuba. But this was not enough: he was in Europe among the first to land in Normandy, on the beach where once again he could see soldiers falling, swept away by machine gun fire and calling for their mothers as they died, and he came into Paris with the partisan avant-gardes and drank pastis in the shade of tree-lined avenues. More medals, more prizes for journalism. There is no war in his lifetime in which he was not decorated for valor and courage and there is no war about which he has not written, that did not enter his short stories and novels. After the war, his fourth marriage, to Mary Welsh.

The hidden hope

Photographs of him in the 1950s show an imposing, proud man, surrounded by hunting trophies in Africa or gigantic fish, astounding marlins fished out of the ocean. A man who has won the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for literature, envied by everyone for his writing skill, a man whose dialogues everyone would like to imitate. Next to him are his wife, with Gary Cooper and Spencer Tracy, the leading actors in films taken from his books, and native guides and hunting dogs. Great Wise Papa, they call him, whose weight of wisdom makes him seem older and whom glory renders resplendent with elastic and powerful strength, while the idea of suicide slowly makes way, but without too much resistance, in his mind where the words suddenly seem forced and “I can’t write any more, there’s no reason to live,” he confided in a doctor. But he can’t help writing, and traveling, and drinking, and hunting, and living everything, as exhausted as he was frenetic. Mary saved him more than once. Until that evening–he was 19 days short of his 62nd birthday. And from the barrels of that shotgun which had shot at elephants and lions, buffalos and gazelles came the shot that burned up Hemingway and all his lonely and aching characters, because they were full of love that they didn’t know how to communicate and full of desire for truth and for something pure that they didn’t know how to encounter. With the one, unconfessed, hidden hope that something might happen, that an adventure might occur that not only was worth living in the instant, but that could give meaning and purpose to all the other instants, the ones that come before and the ones that will come after. An intuited flash in the pity of the old fisherman who embraces everyone and loves everything, the boy, the fish, the sharks, the sea. And has pity for everyone in his defeat. But he too, the old fisherman, goes to sleep and dreams, and he dreams no longer of storms, or women, or great events, or big fish, or fights, or contests of strength, and not even his wife. But he dreams of places, the white cliffs of the islands, the ports and harbors and lions on the beach playing like kittens in the twilight.

Recommended Bibliography

Hemingway’s life-long production, which includes short stories, novels, magazine and newspaper articles, is practically boundless. From the age of 19 to 61, he never stopped writing, and when he stopped he shot himself. We recommend the following as a guide to reading, even though it is partial like every recommendation:

The Sun Also Rises (1926), considered the manifesto of his generation.

A Farewell to Arms (1929), the tragedy of war.

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), the war in Spain and the sense of a common destiny.

Across the River and Into the Trees (1950), nostalgia for a “place” where one can be happy.

The Old Man and the Sea (1952), outstanding; the synthesis of the writer’s pietas and feeling about life.

Fundamental to an understanding of Hemingway and an appreciation of his powerful style and sense of dialogue is the complete collection of 49 stories (written between 1921 and 1936) and the play The Fifth Column, written during the war in Spain.

Hemingway’s favorites were: “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” “In Another Country,” “Hills like White Elephants,” “Something Called Nothing,” “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.”

Published posthumously were:

A Moveable Feast (1964)

Islands in the Stream (1970)

The Garden of Eden (1986)

Excerpts from His Works

Kilimanjaro is a snow covered mountain 19,710 feet high, and is said to be the highest mountain in Africa. Its western summit is called the Masai “Ngàje Ngài,” the House of God. Close to the western summit there is the dried and frozen carcass of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude.

Just then the hyena stopped whimpering in the night and started to make a strange, human, almost crying sound. The woman heard it and stirred uneasily. She did not wake. In her dream she was at the house on Long Island and it was the night before her daughter’s début. Somehow her father was there and he had been very rude. Then the noise the hyena made was so loud she woke and for a moment she did not know where she was and she was very afraid. Then she took the flashlight and shone it on the other cot that they had carried in after Harry had gone to sleep. She could see his bulk under the mosquito bar but somehow he had gotten his leg out and it hung down alongside the cot. The dressings had all come down and she could not look at it.

(from The Snows of Kilimanjaro)

The crowd shouted all the time and threw pieces of bread down into the ring, then cushions and leather wine bottles, keeping up whistling and yelling. Finally the bull was too tired from so much bad sticking and folded his knees and lay down and one of the cuadrilla leaned out over his neck and killed him with the puntillo. The crowd came over the barrera and around the torero and two men grabbed him and held him and some one cut off his pigtail and was waving it and a kid grabbed it and ran away with it. Afterwards I saw him at the café. He was very short with a brown face and quite drunk and he said after all it has happened before like that. I am not really a good bull fighter.

(from The First Forty-nine Stories)

It was a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada. … After all, it is probably only insomnia. Many must have it.

(from A Clean, Well-Lighted Place)