David

In the Old Testament the figure of the King embodies the People and forms one thing with it. The example of the second King of Israel. His mission for the greatness of the People, his great humanity at grips with human history and misery.I came across the figure of King David in the course of my work on a new poetic version of the psalms that the publisher Marietti commissioned from me last year (Poesia dell'uomo e di Dio). I already knew that many psalms are ascribed to David as their author and that, notwithstanding the lively philological discussion on this, his twofold image as King and poet is central to the history of the Hebrew people. Beyond this, and what every Christian knows from hearing the readings at Sunday Mass and the odd bits of information picked up here and there, I knew very little.

I knew that Dante places David in Paradise at the center of the eagle-eye of the blessed that looks at God's light (according to legend the eagle is the only creature that can look directly at the sun), and I remembered that the author of the Divine Comedy, according to authoritative exegetes, saw himself as the new poet David. Furthermore, in Dante's texts there is no lack of references to the figure of David: while he dances "più e men che re" ("more than a king and less") (Purg. II), "king and humble psalmist".

I later discovered that Boccaccio made Petrarch a gift of the psalms with a commentary by St. Augustine and that the poet of the Canzoniere (and of some Penitential Psalms) wanted that book "by day always in my hands and by night and in the hour of death beneath my head." Nietzsche said that nothing in the whole of literary history was comparable to that Hebrew poetry. On the work of David and on the man himself an infinite band of poets, artists, writers, and musicians have worked and continue to work.

Love and sin

But poetry, even such powerful poetry as that of Dante, only sketches and introduces reality.

David, king and poet, appears on the human and historical horizon of the Bible as a giant of a man. It is not by chance that in order to comment on what sin is St. Ambrose, the author of a splendid Apology for the Prophet David, takes up the question speaking of St. Peter. Then the moment when Jesus asks him if he loves him he switches to the contrition of David, who was guilty of murder and adultery. "A great love," writes Ambrose, "remits sin." Ambrose elsewhere "uses" David and his ups and downs (even his faults) as symbols to interpret the mystery of the Incarnation, in opposing the Arian heresies of his time. The words of David's Psalm 50, Miserere mei, found a place not only in Dante's Purgatory, but in the sense of sorrow that every Christian is educated to discover in the Church's liturgy. The number 50, according to the exegetes, is given to this psalm because it is the number of forgiveness: it is the number that appears in the parable of the two debtors, and is the number of years between one Jubilee Year of mercy and the next.

About David, as about all great personalities, legends and various and fantastic interpretations have flourished: that he was a reincarnation of Orpheus, a demi-god of antiquity; that he was not one single person, but the grouping together of a series of kings (David would be a word like "Tsar"); that he had three hundred children. Paolo Flores d'Arcais, participating in a recent convention on the figure of David, did not begrudge him an anodyne laicist homage.

Chosen by God

The Bible tells us of this fair-haired young man, the last born of his father, who is pointed out by Samuel. David is 14 years old and in the sun-drenched fields of Bethlehem is secretly anointed king by the prophet. We are about twenty years before the year 1000 BC. This choice remains a mystery. For sure, as an acute biographer of David has noted, in those long days and nights spent in the empty countryside with his flock, the young shepherd-poet must have matured in his powerful relationship with the God whose hands had created the heavens and fixed the stars, with the God-"shepherd."

He is invited to the king's court so that he can cheer up king Saul, so sullen in his infidelity to God and tormented by an evil spirit. For news of the talent of this poet, who invented his own instruments, had reached the ears of the king's son, Jonathan.

While at court he became a warrior. He gave proof of his courage and of having God on his side. The celebrated episode of the defeat of Goliath represents his entrance into the inner circle of the people and the court. For ten years David is in the king's service as a soldier. Saul's daughter, Michal, falls in love with David and the king agrees to their marriage. Meanwhile the people begin to have a preference for David and rumors begin to circulate in which David is praised for killing tens of thousands of Philistines, while Saul has "only" killed thousands. This and other facts arouse profound envy in Saul, who is already anguished by the thought of his own imminent death, prophesied by Samuel. After the wedding, according to Saul's secret plan, David must die, but the plan is foiled by Michal. David however is forced to go into exile and is separated from his beloved Jonathan.

The exile

The period of exile is one of battles, betrayals, necromancies, the fathering of many children, and of secret ambushes laid in order to convince Saul that David bears him no hatred (on two occasions, in fact, he spares Saul his life).

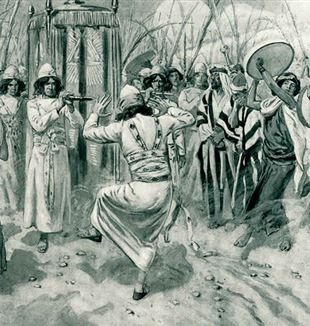

The two Old Testament books of Samuel tell of this gripping adventure. Saul meanwhile goes through a bitter decline, abandoned one after another by "his" prophet, by God, and by the people. After a number of years in exile and after lamenting the death of king Saul (who kills himself after losing a battle) as well as that of Jonathan, David is able to become king himself. He has with him the Ark of the Covenant, which he finally brings to Jerusalem, the city he establishes as his capital. It is then that one of the most significant episodes takes place. David went before the Ark "dancing with all his strength," undressed and merry. His first wife, Michal, is shocked and reproves him for having made a fool of himself, but David replies that he danced for God and cares not for the opinion of high-minded people like her, but that of his People who loves the Lord. This image of the poet-king who dances before the Lord will live forever in iconography.

David's gratitude to God is expressed in the great words of the Psalms and in those pronounced after entering Jerusalem, "Who am I, my Lord, and what is my house that you have raised me up so high? Yet all this seemed good in your eyes, Lord God, you have wished to extend your promises to the house of your servant into the distant future…. What more can David say to you? You yourself Lord, have chosen your servant. To keep faith to your word and the wishes of your heart you have done such a great thing and revealed it to your servant. For you are great, Lord God… There is none like you. And what people on earth is like your people Israel? Was there ever a people whose god set out to redeem them and make them his own people, making their name great, working great and terrible things for them…? For you have constituted them as your people, Israel, for ever."

He who pronounces these words is the same man who composed the magnificent Psalm 8.

After re-entering Jerusalem as King, David calls for the last descendent of Saul, Meribbaal ("the man with crippled feet"), Jonathan's only surviving son, who had fallen on hard times. He welcomed him and had him eat always at his table. Despite all the battles and hatred, David preserves his sense of belonging to a people and to its concrete history.

From then on, though growing in power and popularity, David will see his life and his reign disrupted by what he holds most dear, his children and his loves.

A human story

David, a man of great love, for a sinful love will understand the bitterness of being far from God. This is the well-known story of the murder with which he stains his hands in order to possess the beautiful Bathsheba. The son born to her will die. God will send a plague. On that occasion God has proposed three possible punishments on the kingdom, three years of famine, flight before his enemies or three days of plague. David decides that it is better to fall into God's hands than into man's, since He is great in mercy.

His first born son Amnon will do violence to his sister. He will be proud. His other favorite son, Absalom, will go to war against him. It is a history of clever counselors, of untamed passion, of about-face intrigues for the sake of power. A human history of mud and blood. One of the dramatic climaxes of David's life is the killing of Absalom by his army commander. Although Absalom was at war with him, David had asked for him to be spared. When he receives the news he weeps, overcome with terrible grief. His servants do not understand and reprove him. Once more the king is all too human.

At the end of his life, David begins to feel the chill of time and of his grief. He can no longer get warm, so his servants search the whole kingdom for a virgin who can sleep beside him and warm his old body. They bring him Abishag. The old king had no intercourse with her. This image of the old king who needs to be kept warm has passed into history, not only as a theological sign, but also as an emblem of power that is not sufficient to make a man feel the warmth of life.

David lived long enough to see the rebellion of another of his sons, the handsome Adonijah-whom he never wanted to put to death, though he evidently aspired to a kingdom that was not his right-and to witness more bloodshed. He had been told that his would not be a kingdom of peace. Finally he acquiesced to the request of Bathsheba to nominate his son by her, Solomon, as the new king. With Solomon came a period of great peace in Israel. According to tradition in 970 BC David slept with his fathers after reigning over Israel for forty years.

An evangelical scholar, Samuel Amsler, wrote of him, "David arose in one of the key moments in the Old Testament where the mission of Israel and God's work of salvation converge and complete each other. Here is where David arises again today as the Old Testament's witness to point out to the Church the unique and decisive role of a certain Jesus."