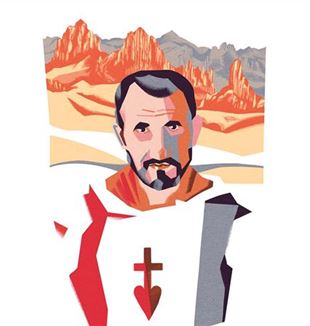

De Foucauld: The rain will come again

His life was marked by the movement from emptiness to presence. His work on Tuareg language and poetry was permeated by wonder. What did the soon-to-be-canonized French missionary find in the "desert”?Fall 1911. Charles de Foucauld writes slowly by lamplight. The nights in the Sahara are cold and, were it not for his hand moving across the paper, the man might look like a ghost, wrapped up under a pile of blankets. The refuge of Assekr, where Foucauld moved a few months ago, is 2,900 meters above sea level in the Algerian Ahaggar massif. Everything is silent. Nothing distracts the hermit from his work. What is he writing about? Let's quietly get closer and take a look.

"Edel: active verb, "to hope in" [God, or a person] (is constructed with an accusative). // By extension "to arrive by night at a place; to arrive by night at a person's house." It is used in this sense whatever the reason for arriving somewhere or at someone’s house at night, whether they wait for you or not. By extension: "begging" (asking alms [something] from [someone], is constructed with two accusatives). It is said of the poor who are beggars."

Edel is a word in Tamasheq, the language of the Tuareg. Charles de Foucauld (1858-1916) was a French priest and missionary. Beatified by Benedict XVI in 2005, he will soon be canonized by Francis after the official recognition (on May 27, 2020) of a new miracle that took place in 2016. I imagine Foucauld as he devotes himself to compiling his Tuareg-French dictionary. Composed between 1914 and 1915, it consists of 2,028 handwritten pages in fine handwriting, illustrated with minute drawings by the author himself. Even today, Foucauld's text is indispensable for ethnologists who want to delve into Tuareg culture. But Foucauld also found time to collect six thousand verses by Tuareg poets, which he translated and arranged into an anthology.

Where did this impetus come from, this ability to make deep contact with a completely different culture? Charles de Foucauld was of noble origins. Orphaned, raised by his grandfather, he pursued a military career and led a rather dissolute life during his youth, but always with a veil of melancholy. He needed to push himself, to seek emptiness. In 1883 he set out on a journey through the interior regions of Morocco, where no European had set foot. His ethnographic studies earned him a gold medal from the Geographical Society of Paris. Contact with the Islamic religion left him in wonder, attracted to "something greater and truer than worldly occupations." He converted to Catholicism and became a Trappist. He later moved to Nazareth, where he worked as a servant in a monastery of Poor Clares. In 1901, after his priestly ordination, he returned to the Sahara, first to Béni Abbès, then to Tamanrasset and Assekrem.

I came across the figure of Foucauld while doing research for a novel. At first I was amazed by his tension toward God, his capacity for abandonment, even though his absolute radicality seemed distant from my own experience. But a few months later, during a period when everything was difficult for me, from writing to daily chores, I intuited the meaning of the desert. That great absence, that immense Saharan space was also opening up in my life: at work, in my family, while waiting at traffic lights or having dinner with friends. The emptiness was not necessarily a sign of anguish; rather, sometimes it was an invitation, a sign that I should not give up waiting for fulfillment.

Foucauld's life consists entirely of this dynamic, of this inexhaustible search for the void to be visited by a Presence that fills and exceeds expectations. The Tamanrasset missionary was aware that he was within the Church, inside "the adventure of God's love." He never succeeded in converting anyone or founding a religious order. But there he was, in the midst of the Tuareg, showing them Jesus through the loyalty of his own friendship and offering himself as a "universal brother." Today there are many experiences of faith that draw on Foucauld, including the Little Brothers and Little Sisters of Jesus. It can be said that the seed has germinated. And if Tuareg culture and language have been saved amid African political upheavals, they also owe it to Charles de Foucauld.

Carlo Ossola, a scholar and professor of literature, writes that "Foucauld's desert is simply listening to creation." Therefore, one must consider his dictionary as "one of the most luminous hymns to the beauty of creation," in which "every word is a station of contemplation." The language of the Tuareg is attentive to the nuances of light, to the minimal sounds of the Sahara. Foucauld listens and watches. The word tit means simultaneously "eye," "spring," and "flower"; tésersek is a small ray of sunshine that manages to penetrate a dark place; amagar designates both the stranger and the guest, since it would be inconceivable to meet a stranger and not offer them food and lodging.

Foucauld lived in the age of colonialism, and precisely because he had breathed that atmosphere, his dictionary and poems are an extraordinary statement of openness and gratuitousness. Pope Francis called Foucauld "a man who overcame so much resistance and gave a witness that has done so much good for the Church." Among the "resistance” he faced was the idea of converting the Tuaregs at any cost, imposing a cultural model. Instead, Foucauld understood that he had to limit himself to the essentials, namely love. Bringing Christ to the Tuaregs meant, first and foremost, loving them for who they were.

Before his death, murdered by a band of looters in 1916, Foucauld shared everything with the Tuareg. He was also aware of the esuf, the risk of deep solitude that in the desert, in any form of desert, can become deadly. His dictionary counters this danger as a form of memory and sharing: how can we not find spiritual meaning in the verb żegżen, which means "to rely entirely on someone" and, by extension, "to surrender oneself to God." Even today, scientists question how Foucauld managed to learn tamasheq in such a short time. He listened to hundreds of poems about war, love, nostalgia, the celebration of the landscape or praise to God. Struck by unexpected beauty, he translated them into French.

Let us take a song by Moūssa ag Ämāstan, for example. Composed in 1891, it expresses the magnificence of creation: "Men, fear the Most High / who created Äouharedj and the Tidekmār mountains, / who created the narrow lands that exhaust camels/ [...] / and the valleys of Ähohogh, Ahtes and Tidjīdial. / (...) / Above you he created the moon and the stars; / he made the day with the sun, the night with frost. / He placed dunes in the valley of Éghergher; / he diversified the country: he put water / in the valley of Äbdenizé, where the people of ancient times dug wells, / and this water was drunk by the beautiful women / who came from the valley of Ens-Idjelmāmen and the region of Oūnān (...)." The mention of "beautiful women" is the sign of the skillful transition from the cosmic to the amorous sphere. The Tuareg poets, just like Foucauld, were enveloped in the emptiness of the desert; their poems are therefore filled with names. In the territory they similarly sense the hidden presence of God and the gaze of a beautiful woman in the evening before the camp fire.

In another poem, a woman evokes the beauty of her beloved through nature. Kenoūa oult Amāstan, born in 1860, describes her man thus: "This year, I saw / a hill of moss with a thousand colors; / the grass was golden and grew with vigor; / honey mixed with butter fattened the earth; / milk flowed and bathed the hill, enclosed in silver meshes." The mention of "silver meshes" turns the landscape into a Tuareg warrior.

Read also - "The universal brother"

In general, in the tamasheq language, every landscape, every atmospheric phenomenon becomes a movement of the soul. The word aġenna, which refers to rain and water in general, "is used in expressions such as 'the rain will come again' or 'fresh and abundant grass will come again'"; and these, Foucauld notes, are also "phrases you say to someone who has wronged you or who is discouraged, in the sense of ‘you think I suffer because of your mistake; no; never mind; good days will still come for us.’” For that matter, the verb etteb, meaning "to fall drop by drop," is also often used figuratively, to express ardent love: "Koūka tettāb dar oul in... meaning Koūka falls drop by drop into my heart (Koūka seeps deeply into my heart; I ardently love Koūka)."

The movement from emptiness to presence distinguishes Charles de Foucauld's life. His dictionary and poems are tangible signs of this, permeated by attention and wonder. Despite difficulties, Foucauld never stopped sowing, certain that the days of harvest would come. In this sense, the noun emedel seems tailor-made for him, denoting both the beggar and the man who trustingly abandons himself to God.