"Karol, do you love me?”

On May 18, one hundred years ago, St. John Paul II was born. A man and a pastor who changed the history of the world and of the Church, from the Solidarnosc epic to the days of his illness. Always carrying the answer to that question within his heart."Karol, do you love me?" These three words express everything about a pontificate and a man's life. It was Joseph Ratzinger who pronounced these words during John Paul II’s funeral, paraphrasing Jesus' question to Peter; Ratzinger, the iron cardinal, the refined theologian or more simply "the friend who always tells the truth", as Karol Wojtyla called him. The truth was that nothing could be understood of the Pope from the East without understanding his answer to that question: "Lord, you know everything. You know that I love you." But the depth of things were better grasped later.

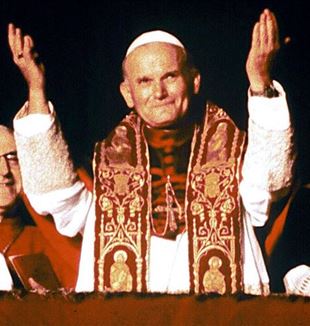

The beginning, in 1978, was an epic. Had anyone ever seen a handsome Pope who systematically and cheerfully violated the rules of protocol, coming down from the altar to address the crowds blocked behind barriers, hugging and greeting them? How had he escaped the networks of the Polish communist regime to reach Rome, with his Italian full of errors and sympathy? Who was Karol Wojtyla, who thundered from the throne of Peter proclaiming "Jesus Christ, center of the cosmos and history", who invited us not to be afraid, to trust Him?

The matter immediately became serious. After John Paul II's first trip to Poland in early 1979, a workers' union, Solidarnosc, was born in the shipyards of Gdansk in August 1980, destined to make history. Incredible images began to spread throughout the West. The photos of John Paul II hanging on the gates of the occupied factories were something that had never been seen or imagined, a unicum that no refined analyst could ever have imagined. The Poles had accepted the invitation and decided to trust it. What interrupted this too fast sequence of history was the attack on the Pope in St. Peter's Square. On May 13, 1981, a cloak of anguish and bewilderment fell upon Rome, comparable only to the day of Aldo Moro’s kidnapping and the murder of his escort. John Paul II did not die and history was again in motion towards the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and – God knows how to be ironic - the lowering of the red flag upon the Kremlin on December 25, 1991.

For many, the history and the peculiarity of the Polish pontificate ends here: the Pope who defeated Communism. Instead, it was only the first part of a bigger and more successful story. The story of an apparent defeat. Since 1992, the physical condition of the Slavic Pope - prophesied in the mid-nineteenth century by poet Juliusz Slowacki, "strong and daring like God" - began to deteriorate progressively as the world's health worsened, to offer the image of a body that seemed to have taken upon itself the fatigue, pain and evil that it had encountered upon its pilgrimage.

Two windows dominated the scene, that of the Gemelli Polyclinic in Rome and that of St. Peter's, from which John Paul II thundered against the Rwandan genocide and then against the war in Bosnia. The latter was an especially bitter wound. In Europe, at the end of a terrible century, the evil of war and racial discrimination resurfaced violently in the Balkans. Once again, men revealed that they were incapable of learning from their own history.

Thus, a century ends and another begins, and the step was not that “crossing the threshold of hope” sponsored by John Paul II, who, in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, with a broken voice, during his Wednesday audience, reflected upon the mystery of man's heart capable of so much evil. The Pope who lived under Nazism and defeated Communism was once again forced to pose, in a dramatic way, the question that marked his whole life and pontificate: what is the limit of Evil? Who can stop it? This was same question that Karol Wojtyla asked himself at the age of twenty. He once recounted this to a group of young people he met in the Vatican, explaining that his priestly vocation was born in the years of the Nazi occupation of Poland, precisely from the human need to find an answer to the horror of the time: "In this evil, in these tragedies and immense sufferings we had to look more deeply for a light...in this darkness the light was the Gospel, it was Christ."

Again, during his last trip to Poland, John Paul II remembered with a smile that young man who, in those years in Krakow, on his way to work as a factory worker, passed the church of Sister Faustina and stopped to beg for Divine Mercy. As the same boy who would become Pope would later affirm, this is the ultimate limit of Evil: the Mercy of God who offers to every man the possibility of being forgiven, of getting up and choosing that Good that no Evil manages to destroy definitively. That Light that the darkness of history cannot extinguish. Did John Paul II really believe that? Yes, he had faith in the merciful Jesus who had accompanied him all his life and, therefore, he also believed in men, despite everything. He also believed, as Joaquin Navarro-Valls recounted, that they were capable of great things, and for that reason it seemed appropriate to ask them to do great things. Canadian Cardinal Gagnon recalled that once, when asked what to do against the people in the Curia who opposed the Pontificate, John Paul II replied: "Nothing." And to the dismayed cardinal who asked why, he explained: "I believe that men can change."

How naive, one would say, if it were not the only real hope for personal life and for history. And to understand, one has to have looked into the face of the men and women who would flock all over the world to see him: those who, silently crying, welcomed him on their knees in Vilnius Square, in Lithuania newly liberated from Communism; in war-torn Lebanon where they bathed him with flowers; in Africa where people would go in amazement to see a good muzungu who remembered them, and those in Fidel Castro’s Cuba who sang "Juan Pablo querido, jamás serà vencido" in the streets. The list is long and includes all those who, in the extraordinary and incredible days of his death, came to Rome because they knew the answer to that question "Karol, do you love me?". Something hard to forget.