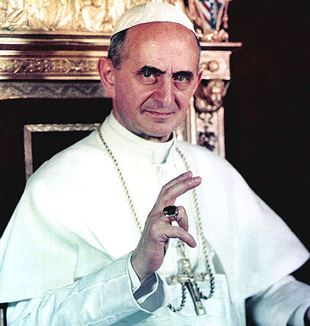

Paul VI: Witness and Teacher

On October 14, His Holiness Pope Francis canonized the Pope who passed through one of the most tormented periods of recent history; Pope Paul VI who, giving all of himself, was always “full of joy.”When, four years ago, Pope Francis beatified Paul VI, he said that Paul VI was an untiring apostle, the pilot of the Council, a courageous Christian. Now, on October 14, in Saint Peter’s Square, Francis will proclaim him a saint along with Oscar Arnulfo Romero, the martyred bishop from El Salvador. Already this juxtaposition tells us something. In some way, in fact, even Giovanni Battista Montini was a martyr, because he shared the Calvary of his friend Aldo Moro. He was also a witness, standing in opposition to the “smoke of Satan” (about which he spoke in the 1970s…) and to the world; he was the object of a campaign of hate and violence inside and outside the Church, above all in the last years of his Pontificate.

This engagement by Paul VI with history was intense and profound, inspired by a great anxiety to reform the Church, in the new and dramatic awareness that the modern world, modernity, was turning its back on Jesus Christ and on the things that come from Him. Already in 1934, Cardinal Angelo Scola tells us in his recent book interview, Ho scommesso sulla libertà [I Have Bet on Freedom], the young Father Battista wrote: “Christ is someone unknown, forgotten, absent from the greater part of Italian culture.” The son of one of the founders of the Italian People’s Party, a man in contact with the great protagonists of the Italian Catholic world in the 20th century, Montini, as Juan María Laboa writes in his Paolo VI, papa della modernità nella Chiesa [Paul VI, the Pope of Modernity in the Church], “in attacking evil, advised us to denounce its motives and its consequence, but not the people involved.” He says about the Pope: “We never direct offensive words at souls, because we desire to save souls, to bring them to Christ, and not to distance them from Him.” Certain others before him, beginning with his beloved predecessor John XXIII, had noticed, even dramatically, the problem of the new challenges of a secularizing modernity in Italy and outside of it: from the English poet T.S. Eliot to the Frenchman Charles Péguy, to the great Italian-German Romano Guardini and even Father Giussani. But it would be Montini’s task to face this turning point in history, an unexpected and violent turning point, from the See of Peter.

Martyrdom means witness. For Paul VI, it is the concept of witness that is the key for a renewed presence in the modern world. In his splendid Apostolic Exhortation from 1975 Evangelii Nuntiandi, taken up again by Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium, he writes: “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses” (n. 41). The phrase was a citation of another talk he had given the year before, at an audience with the Pontifical Council for the Laity on 2 October 1974, where among other topics, he spoke about Movements in the Church.

On that occasion, Paul VI explained that “We can sum up in four points the reasons why today’s world is looking for a true witness to Christ.” The first: modern man, even if he is submerged in material things and goods in an unprecedented way in modern history, “seeks the invisible and immaterial.” Second: “Men of this time are fragile people who easily understand insecurity, fear, and anguish.” This point impressively still resounds today. Third point: “The new generations want to encounter more witnesses to the Absolute. The world is waiting for the presence of saints.” Even this consideration appears very true to us today: the world is looking for inspiration, positivity, the witness of holiness. The fourth and last point: “Modern man poses to himself, often in a painful way, the question about the meaning of human existence. What is the purpose of freedom, work, suffering, death, the presence of others?”

The year 1974 is the same year when in March, just before Easter, Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote an article that was not immediately published and would only later be published in his Scritti corsari [Freelance Writings]. Pasolini recounts: “I saw yesterday (Good Friday?) a group of people in front of the Colosseum: all around was an enormous presence of police and guards. (…) It was a religious function where Paul VI was going to speak. There was barely anyone there. I could not imagine a more complete failure. People no longer feel not just the prestige, but not even the value of the Church. The people have now renounced even one of their most blind habits. For something much worse than religion, no doubt.”

We are on the eve of the referendum on divorce, and Pasolini marvelously is describing an “anthropological revolution” that dismays him. The Pontificate of Paul VI began on the wings of the conciliar renewal, but also on the legitimate optimism inspired by a lasting peace after the Second World War (coincidentally, but symbolically, the first official visit to the new Pope Montini, elected on 30 June 1963, was with the American president John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who visited Rome on 2 July). Then, starting in 1968, it developed into a dramatic confrontation with a contemporary culture that was continually more aggressive and hostile to the Pope and to the Faith.

If in 1974, in fact, there was “barely anyone” at the Via Crucis, it was because for at least six year we had been seeing an unheard-of rupture. Today, critics and historians, whether they be Catholic or secular, recognize in 1968 the decisive year when the critiques within and outside of the Church came to question the faith itself. Giselda Adornato writes in her monumental historical and spiritual biography Paolo VI regarding this moment: “Two fundamental concepts were challenged: truth and authority. And, for the first time, this happened also inside of the Church and sometimes on the part of theologians at a high level.”

In that key year, Paul VI saw clearly in the post-conciliar debate an instinct toward “self-destruction” that no one expected. He explained to his friend Jean Guitton (in the Dialogues with Paul VI): “Instead of separating the teaching of the Council from the doctrinal patrimony of the Church, we should see how they can be integrated, how they fit together and how they give a witness, development, explanation, and application to each other.” It was the year of Humanae Vitae and the Credo of the People of God, solemnly proclaimed on June 30 at the conclusion of the Year of Faith. In his general audience for December 4, he would speak about the “integrity of the revealed message”, saying: “On this point the Catholic Church is jealous, severe, demanding, dogmatic. She cannot be otherwise.” In his personal notes, the Pope wrote: “A new period after the Council. Is our service over? (…) Maybe the Lord called me and keeps me in this service not because I am suited for it, nor so that I can save the Church from its present difficulties, but so that I may suffer a little for the Church, and so that it becomes clear that He alone can guide and save her.”

We catch a glimpse of a double itinerary that is “dramatic and magnificent”, to cite his Testament, another text which is extraordinary even from the literary point of view: on the one hand the aggression of the world and even of his ecclesiastical “friends”, who attack the Pope, and on the other hand the personal purification and the theological deepening of the successor of Peter. In the Dialogues with Guitton, we find that the famous observation: “What strikes me is that within Catholicism it seems that a non-Catholic kind of thinking predominates.”

In 1972, on June 29, the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul, Montini affirmed in his homily the feeling that “from some fissure, the smoke of Satan has entered the temple of God.” And he explained: “There is doubt, uncertainty, challenges, disquiet, dissatisfaction, confrontation. People no longer trust the Church; (…) We thought that after the Council there would come a day of sunshine for the history of the Church. Instead, there has come a day of clouds, of storms, of darkness…”

In 1988, Father Luigi Giussani spoke about Paul VI, ten years after his passing, in an interview with the weekly paper Il Sabato. It is a document that retains its usefulness even today. “The papacy of Paul VI was one of the greatest papacies!”, he said to Renato Farina: “It demonstrated in its first part an extreme sensibility—that no one would ever deny—to all the anxious problems that man and society are living today. And he found an answer! He proclaimed that answer in the last ten years of his pontificate.”

In this article, Giussani recalls his experience in 1975 on Palm Sunday: “The Pope had called the youth of all the Catholic groups to Rome. (…) He called everyone. He found himself with just 17,000 from CL.” At the end of the Mass in the Piazza, the Pope called Father Giussani over: “I remember with precision what he said: ‘Take heart. This is the right road: go forward like this.’” And whoever heard Father Giussani speak about the nature of the Church knows that he loved to cite a particular speech by Paul VI. It was the he gave in 1975, on July 23: “Where is the ‘People of God’ about which we have spoken and still speak. Where is it? This sui generis ethnic identity that is distinguished and considers herself by her religious and messianic, priestly and prophetic, character, if you will, where everything converges toward Christ, as its focal point, and which is derived from Christ? (…) It has a name that is familiar to everyone throughout history; it is the Church.”

The abduction and killing of his “friend” Aldo Moro would profoundly mark the final steps of the Pope’s Pontificate and his existence. In those 55 days, what seemed like an entire phase of our history, of Catholics in politics, of the Republic after World War II, even the engagement of Montini’s very person seemed to fall under the ruins of history. Everything seemed compromised, in an irreversible way. Paul VI prostrated himself in front of the executioners, called them “men”, breaking the logic that the ideology of terrorism had imposed. But his incredible defense of the dignity of man and of the Church remains a great and clear testimony. The Pope participated in the sacrifice of Moro and of Italy, until death, but without ever ceasing to point out that “sui generis ethnic identity” for which he had given his life. “My state of soul?”, he asked himself in a page of his diary: “Hamlet? Don Quixote? Left? Right? I cannot guess. I have this dominant feeling: ‘Superabundo gaudio’. I am full of consolation, pervaded by joy in every tribulation.”

In his last homily, on June 29, 1978, he laid out the balance sheet of his Pontificate: “Our office is the same as Peter’s, to whom Christ entrusted the commandment to confirm his brothers: it is the office of serving the truth of faith, and to offer this truth to anyone who seeks it (…) This, my brothers and children, is the untiring, constant intention that has kept us going in these fifteen years of the Pontificate. ‘Fidem servavi’! We can say this today, with the humble and firm awareness that we have never betrayed ‘the holy truth’ (A. Manzoni).”

Today, we have the highest confirmation that this “painful, dramatic, and magnificent” itinerary which he made first of all as a man, then as a priest, and finally as Pope, brought Saint Paul VI to give life to an idea of the Church and an idea of the Christian witness that has a great power of regeneration. Because it leaves space for the work of an Other.

This is what happened in the miracle that led to his canonization. It was a miracle that was verified in the United States: a child affected by a grave illness that was diagnosed while he was still in the womb, so that the mother was told that she should end her pregnancy. He was healed even before his birth. The defense of life (which mysteriously reminds us of Humanae Vitae) coincided with an event of Grace, with a gift of the Lord. As Pope Francis said: “In this humility the greatness of Paul VI shines forth: while a secularizing and hostile society stood against him, he knew how to go forward with a far-reaching wisdom—and sometimes all by himself—to steer the ship of Peter without ever losing his joy and trust in the Lord.”