Fr. Giussani on St. Stephen, 1944

"The lesson of Christmas and St Stephen is a lesson of sacrifice, but what is the way we can be able to live it?" We publish Fr. Luigi Giussani's homily on the Feast of Saint Stephen, 1944.Veni Sancte Spiritus.

Veni per Mariam.

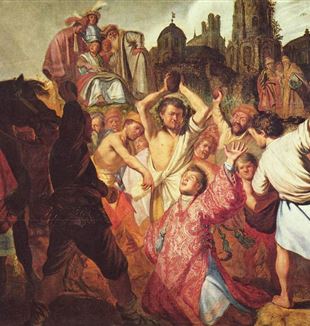

The sacred vestments that the ministers are wearing at the altar are no longer the immaculate white of yesterday. They are red, the symbol of blood. Next to the sweet contemplation of a God-child warmed by His Mother’s love, what a contrast is the vision of Stephen dying under the pelting hail of stones, covered with blood! With what horror our thoughts move from the angels’ song and the affectionate faces of the shepherds to the shouting figures of Stephen’s stoners, throbbing with hatred!

But this juxtaposition is dense with meaning. In the dazzling light that surrounds the stable in Bethlehem, we perceive the majestic outline of the Cross.

St. Stephen was the first to sacrifice his life to follow the Divine Master. The feast of his martyrdom together with the feast of the Holy Birth, whose significance it completes, give us a lesson in sacrifice. His martyrdom shows us a way to help us live this lesson of sacrifice; his martyrdom makes us see its precious fruits.

We shall never understand anything of the true meaning of Christmas if we do not vividly feel that God made Himself man in order to save us: and to save us He had to sacrifice Himself. The Child, whom we contemplate in these days with all the affection and gratitude of believers, bears imprinted on His forehead as a program for His life and an admonition to our thoughtful souls: “I was born to die for you.” When our mothers taught us as young children to make a little vow, on every day of the Christmas Novena, that the Baby Jesus could lie more comfortably in the stiff hay and the straw would not hurt Him–Him who would die on the Cross for our love–our mothers, without knowing it, grasped in a naïve but real way the true meaning of the birth of God into the world, which is that of a profound sacrifice.

Just think: the Infinity of God was enclosed in a minuscule baby’s body. He who created everything that exists humiliated Himself to be born as a miserable son of man. He, the Eternal, Beautiful, Incorruptible wore this flesh of ours, which weighs on us with all its needs, its infirmities, and its condemnation to die and melt away. He, at whose bidding all creatures move as in an immense song in His honor, lived in the midst of little men, treated with the same indifference with which we look at the strangers who pass by us. He, who constructed with marvelous skill all the laws of the universe and who knows even the slightest thought that arises from our hearts in the silent darkness of the night, was treated like a madman. He, true justice, was sentenced unjustly. He, life itself, in whom every life sinks the roots of its existence, died on the scaffolding of slaves. He, Love, whose gaze transformed a whole life, whose word consoled a whole life, and the mere touch of whose clothing healed, was executed like a murderer.

The story of the Child of Nazareth is a history of grief, and it is like a great road along which all men, without distinction, must walk. But there are those who travel it blaspheming; there are those who travel it shaking their heads incredulous and unconvinced; there are those who travel it as a long lament, stunned, without understanding the divine goal; and finally there are those who travel it with religious resignation: a true martyr, that is a witness to Jesus Christ–like Stephen–is one who makes an effort at least to travel it with love. Man’s life is filled with suffering, renunciation, and grief, but man is attached to his earthly life with a formidable instinct. Man builds all his dreams on top of it; he places all his hopes in it; he expends all his toil for it. To keep his earthly life, man would willingly give up the certitude of a happy life in the next world. The grief and suffering that come his way, he makes a great effort to diminish: with a deep-seated instinct of egoism, that tries to unload onto those around him the greatest possible amount of burdens, that tries to subjugate others, that pulls away from the grief and suffering of others as quickly as he can. In this mentality, every sick person is merely tolerated, every poor person is a wretch; whoever weeps is miserable; every weak and powerless creature is worthy of scorn; a meek soul is a disgrace; and every individual with a low social standing is a failure. Thus arises abhorrence at anything that bears a cost, nausea at duty that requires labor, hatred for sacrifice.

At this point, by contrast, it seems to me as though St Stephen rises up from the heap of stones thrown at him to remind us of a page from the Gospel. One day, Jesus dared to say clearly to his disciples that soon He would have to be crucified. Peter took him by the arm and started rebuking him for talking like that. Jesus, training his severe gaze on the disciples, and in a voice that must have left poor Peter feeling pretty badly, said, “Get back, Satan! You are thinking not as God thinks, but as human beings do” (cf. Mk 8:33). Get back, Satan! The distinction between Christ and the Antichrist, between the Christian and the non-Christian lies right in this evaluation of sacrifice and of life. Sacrifice has a redemptive function, because it is the road Christ traveled in order to save us and that each one of us has to follow to get to his true home. Sacrifice has an educative function, because it keeps us from harboring the illusion that life on earth must last indefinitely; it keeps us from confusing the pilgrim’s poor path with the luminous eternal happiness of our homeland. Get back, Satan! Christ had answered Peter; and then raising His voice so that the crowd gathering around Him could hear Him too, He said, “If anyone wants to be a follower of mine, let him renounce himself and take up his cross and follow me. Anyone who wants to save his life will lose it; but anyone who loses his life for my sake, and the sake of the Gospel, will save it. What gain, then, is it for anyone to win the whole world and forfeit his life? And indeed, what can anyone offer in exchange for his life?” (cf. Mk 8:34-37). St Stephen, too, must have heard this thought when he was shoved out of the synagogue and dragged through the streets crowded with the junk dealers’ booths all the way to the palace of the High Priest, to be sentenced to death.

The lesson of Christmas and St Stephen is a lesson of sacrifice, but what is the way we can be able to live it? St Stephen indicates it to us with his impassioned devotion to the Lord Jesus. This is how it could be expressed: “You must not feel alone.” When two faithful spouses feel close to each other, when parents feel close to their children and children to their parents, is not their strength in the face of sacrifice multiplied a hundredfold? When true friends feel united and compact in their Ideal, is not their strength in the face of every obstacle magnified immeasurably? Oh brothers, spouse and parent and child and friends are nothing other than a tangible expression of the Blessed Christ, the invisible but real spouse and father and mother and son and friend, always alert by our side with infinitely solicitous affection to sustain us with His divine strength. But we have to “believe Him.” And believing is not just trusting His words, but adhering to His Person, feeling His Person always present, mastering every activity of our life, every social relationship, even every form of thought and inner feeling. We must be able to affirm that in life we would judge or act in a completely different manner if Our Lord Jesus Christ did not exist: because He is every day our personal Master. “You call me Master, and rightly so, because I am” (cf. Jn 13:13). It is this profound faith in the living presence of Our Lord Jesus Christ that made Stephen the first martyr; there he is, standing straight with his arms uplifted while the hail of stones falls furiously on him: “As they were stoning him, Stephen said in invocation, ‘Lord Jesus, receive my spirit’” (cf. Acts 7:59).

One last reflection is suggested to us by today’s feast. “Lord, we have left everything and followed You” (cf. Mt 19:27), Peter exclaimed once to Jesus. Almost as though he wanted to add, “What will You give us?” Jesus answered the unspoken question: “The hundredfold in this life, and eternal life” (cf. Mt 19:29). The hundredfold in this life! This glory is also earthly: after so many centuries, still today millions of men the world over sing their homage to St Stephen, and his apotheosis rises up like a magnificent cathedral, made of admiration, glory, love, enthusiasm, veneration. But above all, the fruit of sacrifice welcomed on earth is peace. The good of exile is peace, just as the good of our homeland is happiness. I am speaking, my brothers, of inner peace, without which we cannot fully enjoy anything; of inner peace, because outer peace is necessary in any case, since without it, it is much more difficult to maintain the inner peace of the spirit. We are experiencing this today. True peace, the peace that matters and is the great security of the conscience that tries to do God’s will; true peace, the peace that matters and is the profound serenity that each of us can feel, but that is almost impossible to make someone understand if he doesn’t feel it; that leaves us anguish and grief and the anxiety of suffering, but that in the depths of our souls, as soon as we return there, makes us find a faithful resignation, a silent and certain hope; true peace, the peace that matters and is a patience filled with goodness and understanding for others, who are all our brothers and miserable like us. Here is Stephen, receiving his death blow, falling on his knees, and with a final cry full of peace: “Lord, do not hold this sin against them” (cf. Acts 7:60).

May Baby Jesus, through Our Lady’s intercession, give us, just as He gave to His first martyr, the superhuman strength to be able to follow Him on the road of the Cross, which is the law of every life, which is the law of every true love, which is–especially now–the law of true friendship with Christ. He will give this strength to His poor human brothers, whose wretched days give us tangible proof that we are not made for this earth.

To us who have to suffer and don’t want to suffer, us who have to weep and who pour out our tears with impotent bitterness; us who are stripped and tormented, and who rebel with the instinct of wounded beasts to the rude wrenching; us who have to die and who would like to run away from death with dread and horror. May He grant us to suffer in peace, to weep in peace, to feel tormented in peace, to die in peace.

In his vision of the Apocalypse, St John saw in front of the throne of the Lamb, that is of Christ, an immense multitude of people dressed in white, holding palm fronds in their hands. He asked who they were: “These are the people who have been through the great trial; they have washed their robes white again in the blood of the Lamb [that is to say, in the cross and in pain]. That is why they are standing in front of God’s throne. They will never hunger or thirst again; sun and scorching wind will never plague them. Because the Lamb will guide them always to springs of living water, of happiness, and God will wipe away all tears from their eyes” (cf. Rev 7:14-17). Et absterget Deus omnem lacrimam ex oculis eorum. What a wonderful thing! Let us remember St John’s vision, brothers, in our grief, and let us comfort ourselves with the sweet thought that “God will wipe away all tears from our eyes.”

Homily by Luigi Giussani for the Feast of St Stephen

Desio, Italy, December 26, 1944