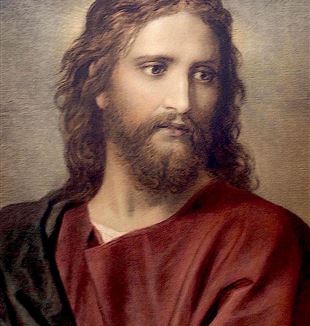

"It Is the Lord!"

The release of the Pope's new book offers a look at the Church's journey and the challenge of His Presence, before which we have to take a stand. Traces offers here some keys to understanding why people touched by grace "make an age."So then, what is the truth about Jesus? This is the question to which Joseph Ratzinger has dedicated his whole life, both as a theologian and as a pastor, but primarily as a man. It is also a question that he himself poses in the second part of his monumental Jesus of Nazareth (Ignatius Press, 375 pages, $ 24.95), taking us from Jesus' entrance into Jerusalem to His Resurrection. In these pages, the scientist and the master of the faith shine forth, but through them there beats the heart of a man seeking the truth, a man who has come across the figure and message of Jesus. This is something that cannot leave one indifferent, since, as Kierkegaard once said, "With Jesus, you must take a position."

From his introduction, the pope–theologian makes his intention clear. He lays bare the bankruptcy of 200 years of exegesis completely dominated by the historical-critical method. If we truly wish to provide a convincing answer about Jesus, one that does not spring from prejudices and ideological interpretations, biblical exegesis must return to seeing itself as a theological discipline, without belittling the demands of historical criticism. Such is the task set forth by the Second Vatican Council's Constitution Dei Verbum. Nevertheless, in Ratzinger's view, as of today, little or nothing has been done in that regard.

From the very first page of the book, the Pope seems to strip himself of the attributes of his ministerial authority. He takes the field in order to carry on a demanding and impassioned dialogue with the principal biblical scholars, both those near to him and those opposed to him. Above all, though, Ratzinger measures himself against the Jesus the Scriptures give us. He wields the instruments of scientific reason with precision, yet always within the great breadth of the Church's faith within which these texts were born. And so, within these pages, the figure that has been disjointed by a certain type of exegesis, dismantled piece by piece until it was unrecognizable, takes on an extraordinary solidity, an impressive capacity to persuade. Faced with this Jesus who is revealed to us, it is impossible to remain a mere spectator. He is Someone who speaks to our lives, who offers them fullness and can therefore call for our conversion.

At times, Ratzinger the polemicist emerges, the one known so well to colleagues and students in the classrooms of Tübingen, Bonn, and Regensburg. Ever polite, always respectful of others, yet devastating in the use of his keenly honed reason, his first target for demolition is the image of Jesus the politician and revolutionary, Jesus the zealot, condemned for trying to lead a violent revolt against the Roman invaders. It is an image that caught on with some forms of theology fashionable in the 1960s and 1970s, which claimed to legitimize the use of violence in order to establish a better world. But zeal for God's house never leads Jesus to violence. "Jesus does not come as a destroyer. He does not come bearing the sword of the revolutionary. He comes with the gift of healing. …He reveals God as the one who loves and His power as the power of love."

An Unheard of Method

The Jesus of the Gospels comes under the sign of the Cross. His Passion and Resurrection would legitimize a claim that scandalized the teachers of Israel. And faced with the numerous invitations–both sincere and deceitful–to confirm His claim with a sign, the binomial of Cross and Resurrection would be the only sign, "the sign of Jonah," He would offer to Israel and to the world. Yet this unheard of method arouses incomprehension and rejection, and not only in His enemies. Peter also experiences that aversion which would continue on in the history of His disciples for centuries. "'You shall never wash my feet' (Jn 13:8) …[Y]ou must not lower Yourself or practice humility!" And Ratzigner says that Jesus must help us to understand over and over again that God's power is different, that the Messiah must enter into glory and lead to glory through suffering, as Peter learned when he saw his anxiousness to fight ending in denial as the cock crowed. He had to learn the humility of following in order to be led where he did not want to go, in order to ultimately receive the grace of martyrdom.

The dramatic tension, achieved through the literary beauty of this text, reaches its peak in the pages about the Garden of Gethsemane. It is there that Jesus experienced ultimate loneliness, all of the tribulation of being a man. There the abyss of evil and sin of all times reached the depths of His soul. There He kissed the betrayer and His disciples abandoned Him. There, says the Pope, "He fought for me." On various occasions throughout the book, he speaks of Jesus' agony and, what is more, he transmits it to us vividly. It is the most unfathomable mystery of this Jesus who is the blessed Son of the Father, the Father whom He calls in His desolation Abba, a word that no Israelite would have used to address the God of the Covenant. He thus demonstrates the intimate essence of His relationship with God. The entire explanation of the prayer in the Garden, with its two petitions, is impressive: If possible, free Me from this hour… but not My will, but Yours be done. "In Jesus' natural human will, the sum total of human nature's resistance to God is present…. [But] Jesus elevates our recalcitrant nature to become its real self."

If the violent revolutionary is a grotesque deformation of Jesus of Nazareth, neither do the images of a goodly rabbi or a simple prophet fit. From His entrance into Jerusalem, His diatribe with the money changers and Pharisees around the temple, the Last Supper and the agony in the Garden, Jesus' mission and His messianic claim (revealed completely in His dialogue with Caiaphas) are painted with vigorous strokes. Here Ratzinger faces one of the issues that seems insurmountable for the modern sensibility and mentality: the issue of "expiation." For today's mentality, it seems unbearable to reconcile the image of a God who is a good and merciful Father with the task entrusted to Jesus of handing Himself over for the sins of all of humanity. Is this really what the texts wished to communicate to us? Or was it rather a later reformulation by the early Church? Here Ratzinger asks us to be willing to not twist the texts to our own rationalist mindset, so as to allow them to lead us beyond our own presumption.

At the Foot of the Cross

The overwhelming reality of evil exists in a form that is palpable for us daily. It is not a reflection, but a fact that contaminates and rots away life in a thousand ways. Would it be realistic, let alone just, to think of a redemption that simply ignored the tremendous weight of this evil, in order to wipe the slate clean? Here, Professor Ratzinger shows his genius for diving into the Mystery and making it comprehensible for us. The reality of evil, which we experience with so much bitterness and impotence in the present moment of our lives and throughout history, cannot simply be ignored. It must be defeated and eliminated. It is not that a cruel God demands an unbearable and excessive payment from Jesus; it is just the opposite. "God Himself becomes the locus of reconciliation, and in the person of His Son takes the suffering upon Himself."

Pascal recreates the scene of Gethsemane by hearing Jesus say (and each of us can make that distress his own): "I spilled those drops of blood for you." Indeed, from the pierced heart of Jesus flow the water and blood that foreshadow Baptism and the Eucharist, the deep fabric of the Church that is born at the foot of the Cross.

Here we must pause to note the extraordinary delicacy, the respect and even tenderness toward the Jewish people, toward our fathers in the faith of Abraham, which issues from these pages. In this volume, the Pope unhesitatingly takes on the central core of the polemic between Judaism and Christianity: Jesus' claim of divinity, the meaning of His teaching, His condemnation, and His execution on the Cross. It is explosive material that Joseph Ratzinger delves into within a context of hypersensitivities constantly ready to be ignited. And yet any reader will finish reading this book with a notable increase in his love for Israel, with a broadened and luminous understanding of the great biblical history onto which the newness of Christianity is necessarily grafted.

We have reached the chapter dedicated to the Resurrection of Jesus, the decisive point of this investigation, according to the author, and it is so because Christian faith stands or falls on the truth of this testimony. The conclusion is emphatic: without the Resurrection, Jesus might have left some interesting traces, some more or less useful ideas about God and man, "but the Christian faith itself would be dead." Only the Resurrection legitimizes and confirms Jesus' claim. Yet what exactly are we talking about? In order to explain this reality that is the basis of the apostolic testimony, Ratzinger speaks of a "decisive mutation," of a "qualitative leap": a breaking of chains so as to enter into a new dimension of existence, a totally new type of life not subject to the law of becoming and of death.

In the final pages of this book, Pope Benedict dialogues with the contemporary reader marked by skepticism and the supposed omnipotence of the empirical sciences, but also desirous of a fullness, of a true life that he cannot manage to imagine and define. And Ratzinger does not hide the dimensions of the mystery. The Jesus who appears to His own is not a reanimated cadaver, but someone who lived from God in a completely new way. He no longer belonged to this world, but He was present in it in a real way, in His own identity. Could it really have been so? Can we, as modern persons, give credit to such a story? Answering this question in the positive is a challenge for the whole Church, one that Ratzinger takes on by starting from the faithful understanding of the stories of Scripture, while at the same time taking into consideration the questions of our time. His conclusion is that science itself cannot close the doors to the possibility of something new, unexpected. And he wonders if creation, at its depths, is not awaiting a definitive mutation, a surpassing of all limits, a secretly hoped for fullness and harmony.

Whatever the case may be, the Resurrection, which is beyond history and opens the door to another dimension, has left a palpable mark on history. The missionary enthusiasm, the bravery, and the drive of that first group of Christians would be inconceivable if something unimaginable had not taken place on the horizon of their experience, something that made them overcome the trauma of Jesus' Death on the Cross. Thus the story of the Resurrection becomes ecclesiology: it gives the Church its form and sends it on mission.

Here begins the time of the Church, which can now understand the drama of the Cross and the announcements that salvation would only take place through the suffering of the Son of Man. Peter in particular realizes his shortsightedness when he stubbornly argued with the Master about particulars. Salvation could not come through the imposition of power, but rather through love that demands conversion.

Close to Us

Thus begins the time of the Church, the time that elapses between the earthly history of Jesus and His glorious coming at the end of time. When Jesus ascends to the Father, He does not forsake His own. Rather, He remains present: "In our own day, too, the boat of the Church travels against the headwind of history through the turbulent ocean of time. Often it looks as if it is bound to sink. But the Lord is there, and He comes at the right moment." Yes, He comes continually in His Word, in the sacraments, in the events of life and the witness of sanctity. And there are moments, the Pope says, in which this coming through people touched by His grace "makes an age," as happened with Francis and Dominic between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, or with Theresa and Ignatius in the sixteenth century. And the book of the Pope who is theologian, scientist, believer, and man who has distilled here the fruit of an entire life, closes with a simple and impassioned invocation "that He give us today new witnesses of His presence, in whom He Himself comes close to us."