One Heart

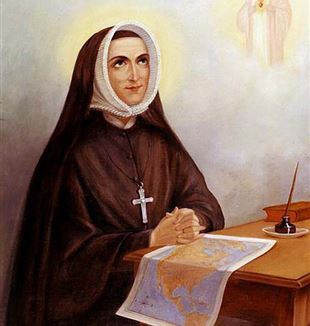

Stalwart and unhesitant, she led a life of adventure and hardship, always at the service of her Society and the Lord, who molded her personality to be a tool of His will, which she followed from the bloody revolution of France to the barely settled landsThe formidable Rose Philippine Duchesne, with her three companions, debarked in New Orleans in May of 1818. She was already forty-nine years old, an instrument forged in the ovens of hardship and persecution. Of exceptionally sturdy stock, this mountain girl was of the right metal for being the spearhead of a harrowing and comfortless mission. But, ultimately, this was not because of her exceedingly robust constitution, or her sharp, clear, and eminently practical mind, or even her implacable disposition, all of which she was graced with in abundance. Rather, she was the right instrument because her heroic nature and indomitable will had been met, conquered, and forged anew by the even more indomitable love of Jesus Christ encountered in the companionship of the Society of the Sacred Heart. As she set foot upon the lands she had so long dreamed of and desired to see, it was with the full consciousness of one who has been sent and whose true strength is derived from her unshakable unity with the company that had sent her. The Cor Unum of the company, under the guidance of their beloved mother and foundress, St Madeleine Sophie Barat, was the very identity of that missionary whose life would mark such a significant chapter in the history of the Catholic Church in America.

Set fast against the towering and sometimes forbidding Alps, Grenoble in southeastern France was a suitable background for the Duchesne family. Rose Philippine Duchesne was born on August 29, 1769. It was a time for causes, and both her father, Pierre Francoise, and his father-in-law were in the thick of it. Die-hard liberals, enemies of the monarchy, hostile to the Church, and active in launching the French Revolution, they nonetheless married women who, with equal ardor, maintained strictly Christian homes. Rose Euphrosyne trained the inflexible will of her eldest child, Philippine, in a love and service of the poor. When her mother objected to her giving all her allowance to beggars, saying, “Philipine, we give you that for your pleasure,” she responded adamantly, “But this is my pleasure.”

Dancing School

Her first years of schooling took place within sight of snow-covered peaks at the monastery Ste Marie-d’en Haut, St Mary’s On High. It belonged to the Visitation Sisters. Philippine became inflamed. She soon began to try always to be first to morning meditation and was often found at the foot of the altar. When a Jesuit from America came to speak of the Indians in Louisiana, she was captivated by a desire to bring the Gospel to the suffering Native Americans. But as soon as her father saw that she intended to join this community of cloistered nuns, he pulled her out and set her in the most secular setting possible–dancing school! But the subtlety, grace, and delicacy of dance could not have been more foreign to her nature, and the five years there left little impression upon her. As one of her sisters put it, she applied herself to dancing as if to an algebra problem, all fierce determination. In 1787, when she was eighteen, she finally succeeded in making a visit to Ste Marie-d’en Haut and refused to come out from behind the grill.

When the revolution broke out in 1789, she allowed her family to remove her to safety and she served them with the same selflessness and hard work that had marked her time in the convent. Soon, however, the nunnery was seized by the anti-clerical government and the nuns dispersed in order to make way for political prisoners. As the defenders of the Church began to suffer and find martyrdom, she began to devote her life more and more to visiting those who were imprisoned and soon to be executed and to aiding the priests who carried out their ministrations in secret. For example, she would go ahead of a priest in the dead of the night to make the sure the way was clear for him to arrive at the house of those needing his sacraments. At great risk, she herself began to catechize the street children. Over the next ten years, she gained an incredible alertness to perceiving needs and seeking to give aid and comfort.

When finally the persecution died down, she did not waste a moment in quickly using her family money to purchase the old convent and, with one companion, moved into the now-ruined structure. She threw herself into trying to recreate what had once been, but to no avail. Though she mightily labored to make the place ready for the return of her companions, few came, and those who did, overcome by the poverty, left.

During this time, at the age of thirty-five, she heard about the new Society of the Sacred Heart from her confessor, and about the founder, Madeleine Sophie Barat. Her confessor suggested that she offer her monastery to this new community. Mother Barat arrived (with two companions) and her entry into Philippine’s life was its most decisive molding force. Though Mother Barat was only twenty-five years old, Philippine saw a life and charism in her that answered all her prayers. For her part, Madeleine Sophie recognized the greatness of this new member of her society. In a letter she chides her older novice for being too tough on herself: “You who love the good St Francis de Sales so much, why didn’t you take his spirit when you were at his school? What gentleness he had with himself and everyone else!” In turn, Philippine made known her great desire, still ardent after all these years, to go to America to serve the Indians. Sophie approved and encouraged her, but saw that before all else Philippine needed to be formed in a communion with her society, to be of one mind, and more importantly, one heart, Cor Unum, with those who had encountered Christ in the same way she had. Thus, it would be another twelve years before consent was finally given. In this time, she became one with the life and spirit of Madeleine Sophie, though always so different in character. In subsequent years, many, including many whom she trusted and otherwise obeyed, would try to induce her to break off from her roots, to “start anew” in America. She never compromised the integrity of her unity with her society for a moment.

The journey to America was a good introduction to the hardships of frontier life that awaited Rose Philippine and her companions. The trip took eleven weeks and was marked by storms. It was with great relief and gratitude to God that the little company arrived in New Orleans. Almost from that moment on, these sisters, and Philippine in particular, would face deprivation, failure, and rejection as they served under the Bishop of Louisiana whose see was a forty-days journey up the Mississippi River in St Louis. As Bishop Du Bourg wrote to them at this time, “You have come, you say, seeking the Cross. Well, you have taken exactly the right road to find it.” When they found the episcopal palace, they found a place which, as Philippine wrote, was “like the poorest farmhouse in France,” without doors or covering for the windows, “in which he lodged four or five invalid priests and shared with them one very small room which did service as dormitory, refectory, and study.” Their conditions were often to be worse.

Frontier Girls

They first settled in a small town outside of St Louis called St Charles. They opened a school for girls that started off with twenty-one students, six of whom lived at the school. The level of education and faith they found among the young girls that first came to them was astonishingly low. Not only did they not know the alphabet, but when the sisters began to speak of the Son of God, the girls showed frank incredulity. They had never heard any of it before. For a while, everyone–nuns and students–slept in one room, drafty and freezing, that served all the purposes of dormitory and school. The priest assigned to them almost died from exposure while sleeping in the corn crib outside! Yet their letters at all times communicate a real joy and gaiety. Teaching materials were more than scarce; they were virtually nonexistent. They worked all hours to keep themselves supplied with the basics, but still had very little, sometimes simply not eating due to lack. The frontier girls, though, did not often complain. And from among these hardy girls they began to receive vocations. This was great news indeed. Before long, with new arrivals from France, they opened up new houses, to the south in Louisiana, headed up by Mother Audé, who was most capable and adored by the students, as well as having the greatest linguistic facility.

Philippine still desired to serve among the Indians, but it would be another twenty years before this happened! And in the meantime, a certain pattern emerged: sickness, disaster, and poverty were ever their companions, yet still they were fervent and glad. Their numbers grew, but mostly through foundations other than those headed by Mother Duchesne. She could not learn the language, was not readily flexible, and always met with difficulty in ingratiating herself to others. It seemed that the foundations never really did well until she moved on to another place. Yet she was always their strength. This was not only because she was in constant prayer, often remaining on her knees in front of the sacrament for up to twelve hours at a time, but also because what mattered most to her was to continue in that communion of love, that accent of life that they received from their society in France through Mother Madeleine Sophie Barat.

Under her Wing

In 1834, the Jesuits, who lacked the funds to come to St Louis, walked all the way from Maryland in order to open an Indian mission. When they arrived, it was Mother Duchesne who took them under her wing and, out of her poverty, came to their aid. In return, it was finally the Jesuits who, in 1841, when she was already seventy-two, invited her and her sisters to come to serve among the Native Americans. She was elated and fulfilled. Though she could not learn the tongue and was too old to work, she quickly became famous among them and received the name “Woman Who Prays Always.” This was to last but a year. She was called back to St Charles where she spent the next ten years growing ever closer to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, praying always, and being a living sacrament of their communion with one another. She died on November 18, 1852, at the age of eighty-three. In the end, what sustained her and allowed her to be a true instrument of God’s grace in the Church was not so much her remarkable qualities, great as they were, but her childlike belonging to a gratuitous gift of companionship. In that unity, in the one heart, is that force and presence that, as the fruit of her life makes evident, renews the face of the earth.

In 1940, Philippine was beatified by Pope Pius XII, and her relics are housed at the shrine dedicated to her honor in St Charles, Missouri. Her name is the first inscribed on the Pioneer Roll of Fame in the Jefferson Memorial Building in St Louis, Missouri.