The Big Apple’s Parish Priest

The death of the Archbishop of New York, a strong reference point for American Catholics. His Irish origin and his profound knowledge of the American environment.Ed Koch was one of the most eccentric and popular mayors New York had in the second half of the century just ending. Cardinal O’Connor was his friend, but he did not hesitate to take him to court when the mayor issued an ordinance on sexual discrimination that would have obliged the Church to obey the municipal administration. O’Connor won the case, and yet their friendship did not suffer. In fact, when Koch had a stroke in 1987, he asked the Cardinal to promise to officiate at his funeral if he died. The Mayor warned O’Connor that it would be a Jewish ceremony, as he was Jewish. But he wanted, nonetheless, for his Catholic friend John to be the one to bid him farewell, and John promised.

The Cardinal never officiated at that funeral, because he died before Koch. But this is one of the many stories that help elucidate why O’Connor became a myth, in New York and throughout America. He was always ready to defend his convictions with clarity, and always ready to make the first move, even toward people with whom he disagreed. When asked who he was named after, he replied with satisfaction, “St. John Fisher, beheaded by the king of England for defending the doctrine of the Church.”

A name that was a good omen for a Cardinal and for an Irishman.

The miracle of St. Rita

John O’Connor was born in a modest neighborhood of Philadelphia, in January 1920. His father Thomas was an artisan, but also a local union leader, and his son never forgot it. His mother taught him another truth that would prove crucial for his future. When John was a child, she lost her sight. She decided that the best treatment would be to pray to St. Rita of Cascia, patron saint of lost causes. The next year her sight returned, and this convinced her son that prayer was the strongest instrument men had at their disposal.

O’Connor took his vows in 1945, and seven years later became a military chaplain, serving in the wars of Korea and Vietnam. He reached the position of Auxiliary Bishop for the Military Vicariate, and was given the rank of admiral. In this post, he was involved in writing a letter from the American Bishops Conference against nuclear weapons, which brought him into direct contact with John Paul II. These encounters left their mark, and in 1983, when O’Connor was dreaming of retiring to a parish in Pennsylvania, he was named Bishop of Scranton. The following year, to everyone’s surprise, the Pope chose him to succeed Terence Cooke as Archbishop of New York. According to a popular rumor, the Holy Father had said, “I want a man like me in the capital of the world.” And O’Connor endeavored not to disappoint him. In 1985 he was given the cardinal’s hat, soon becoming a reference point for Catholics throughout the country.

New York is often considered the media center where every word echoes around the world. From the first moment on the job, O’Connor tried to take advantage of this attention, to spread and defend the teachings of the Church. In fact, his press conferences–which, in the early years, he held every Sunday in St. Patrick’s Cathedral–became the journalists’ favorite appointment, as they anticipated the headlines for Monday’s front page.

To those who called him a conservative, the Cardinal would reply that he was “orthodox in doctrine, but liberal on social issues.” Certainly he was an impossible man to label and was not politically correct, that is, he did not obey the often hypocritical etiquette of public life.

O’Connor often spoke out according to his conscience. He was a strenuous opponent of abortion, and he opposed the death penalty with the same determination. He was contrary to the legalization of homosexual marriages, and even went so far as to forbid meetings of gay Catholics in the Manhattan parish of St. Francis Xavier. However, he directed St. Clare’s Hospital to open the first emergency room in New York for AIDS victims, and in the evenings would go visit the dying who could not even recognize him, washing their faces and hair and emptying their bedpans. He was the friend of politicians, but he never hesitated to criticize when he thought it was necessary. He rebuked Reagan for Nicaragua, Clinton for the Lewinsky affair, Giuliani for inhuman treatment of the homeless, Pataki for the reintroduction of the death penalty in New York state, and threatened excommunication to Mario Cuomo and Geraldine Ferraro, Catholics who were personally opposed to abortion but defended the state’s right to adopt pro-choice policies. When the police killed the unarmed black man Amadou Diallo and New York was on the verge of a racial revolt, he embraced the victim’s parents and organized a meeting with activist Al Sharpton to reconcile the community. And when the hospital staff workers went on strike, he refused to hire temporary substitutes, defending the workers’ right to decent treatment. Even before entering the Archdiocese, he irritated Jews by comparing abortion to the Holocaust. But after his death, James Rudin, Director of Inter-Religious Affairs for the American Jewish Committee, called him “a prince.” For the Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, O’Connor “said very brave things,” and was thus becoming one of the protagonists of the new dialogue between Catholics and Jews.

A good priest

And yet he was also a man of wit and humor, capable of self-criticism to the point of admitting that “sometimes I have said stupid things, and if I could I would erase them.” For example, he would have liked to hide the book published in 1968 in which he defended American policy in Vietnam.

Last August, the doctors discovered the brain tumor that would lead to his death, and forced him to undergo an emergency operation. In September, returning for the first time to St. Patrick’s Cathedral after his operation, he deflated the tension among the faithful by saying, “You have organized a very nice celebration for my funeral! I loved every minute of it.” He called his illness “a gift, because it helps bring me closer to the suffering of Christ.”

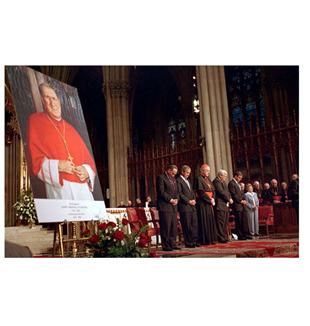

The actual funeral was held May 8th, and it brought to St. Patrick’s all of the America that counts, from President Clinton and former-President Bush to the presidential candidates Gore and Bush junior, courting Catholic votes. While he was alive, O’Connor expressed this wish: “I would like my tombstone to read simply, ‘He was a good priest.’” But he was much more, and there is no way to hide it.

*New York correspondent for Avvenire daily newspaper