Living the Risk of Education

"'The fact that you are at this school is a sign of Christ’s preference for you,' she said...as I rolled my eyes. 'This school is living The Risk of Education!'"After Fr. Giussani’s famous “train conversation” with a group of Italian youth, he realized that growing up in a Catholic culture was not an adequate means to pass on the experience of the Christian faith. A religious proposal that is not tested through experience is rendered a mere “museum piece,” to use Pope Francis’ words.

Allowing students to test what they are taught by “throwing them into the real,” implies that the adult, the teacher or parent, risks their freedom. This is the most dramatic aspect of education, according to Giussani, but also the most necessary.

During my first year teaching at St. Benedict’s Preparatory School, a Benedictine boys high school in the heart of Newark, New Jersey, I was “thrown” into reality and, metaphorically speaking, to the wolves. Trying to establish order, gain the students’ respect, and get them to take the content I was teaching them to heart felt like an impossible balancing act. I complained to my friends about how rough the first year was, until one friend called me out on my lack of attentiveness.

Around the same time that I started my job there, a documentary about St. Benedict’s aired on PBS. My friend, having seen the documentary, was moved by the way that we risk our students’ freedom. Our claim to fame is that “the students run the school.” We never do anything for the students that they can’t do for themselves, which includes leading our daily morning convocation, managing attendance, and serving as mentors to their younger classmates in their groups (a house system that consists of students from all grades).

“The fact that you are at this school is a sign of Christ’s preference for you,” she said...as I rolled my eyes. “This school is living The Risk of Education!” This friend’s insistence made me realize there was something happening at this school that resonated deeply with my experience in CL.

Over the past few years, several of my Movement friends came to speak to my classes, and I’ve invited some students and co-workers to events like the New York Encounter and the GS vacations. Some of the students who attended the vacation eventually asked to start a school of community.

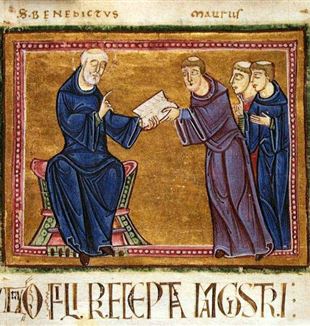

This desire to share my “two worlds” has only grown over time, reaching a peak after an article was published in our local newspaper about St. Benedict’s’ 150th anniversary. One of the monks, who is a dear friend, accompanied the reporter throughout the school and monastery. He pointed out, for the reporter’s benefit, the deep Benedictine roots of our educational approach. After reading the article, I was spurred to communicate in a clearer and more intentional way how similar the Benedictine charism manifested in our school is to the charism of CL.

I decided to invite my friends from both communities to have dinner at my house. I wanted them to get to know each other and to share experiences of what education means.

What struck me most about this dinner was the point of unity I recognized among all of the friends who came. Each person has helped me, in very concrete and specific ways, to approach my work with an open heart and open eyes. Each has become one of my “companions toward my destiny,” as Giussani describes true friendship.

This realization leads me to think of Psalm 133, when King David proclaims “how good and pleasant it is when brethren dwell in unity.” There was a tangible sense of brother and sisterhood among my friends who participate in these charisms. The charisms of both St. Benedict and Giussani are founded on the promise of God’s presence in the flesh...in the gritty, concrete details of work and all of reality. My growing certainty of this promise has enabled me to be open to all of reality, to “test everything”, even when things take a nosedive into chaos (as often happens at St. Benedict’s).

This moment with my friends was the perfect way to end the school year. When I’m not working, there’s a temptation to look at time spent with friends as an opportunity to complain about some of my more obnoxious students, or to distract myself from work pressures. But this dinner was different. This dinner was a moment of gratitude. It was a moment to celebrate the beauty of our work. Best, it was a moment full of the memory of Christ’s preference for me.

Stephen Adubato, New York, USA