Indestructible, stubborn presence

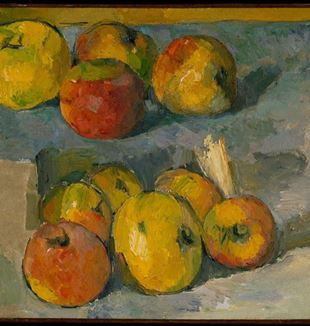

Still lifes, but which enclose the hand of the Creator in their 'being'. Giovanni Testori's "Two apples" and the deep connection with the works of Cézanne and Giacometti.What do the eyes of an artist see in a simple, trivial apple? Rainer Maria Rilke reveals it to us. In October 1907, the great poet from Prague had just visited the Paul Cézanne exhibition in Paris a year after the artist's death. For Rilke, that exhibition had been a true lightning strike, documented in a series of extraordinary letters sent almost daily to his wife Clara. Observing the paintings with apples, a subject at the centre of so many of Cézanne's still lifes, Rilke wrote on 8 October: “They have become simply indestructible in their stubborn presence,” so much so that “their edibility seems to have disappeared altogether.” How to explain this transfiguration? Rilke proposes a hypothesis: “[Cézanne] makes his ‘saints’ out of things like that; and compels them, compels them to be beautiful, to signify the whole world and all happiness and all glory.” In essence, summarises the poet, the apples are “the knot in the rosary at which his life says a prayer.”

Giovanni Testori, who painted the two apples that appear on the cover of the January issue of Tracce, was one of the sharpest and most profound interpreters of precisely Cézanne's painting as an art critic. In 1978, in the aftermath of a historic Parisian exhibition dedicated to the rediscovery of the artist's last period, he wrote two long and impassioned articles for Corriere della Sera and Il Sabato, in which he proposed a new reading of his work. For Testori, the task that Cézanne had given himself, particularly in the final rush of his human and artistic adventure, was that of “putting the image of existence back on track, tracing the hand of the Creator; and in the footsteps left by her, attempting the enormous, perhaps impossible undertaking.” And where to trace the hand of the Creator if not from the 'commonplace', Testori emphasised. Apples are precisely the emblem of this 'common place', "the Promised Land where the most humble and usual forms of life reveal, without losing anything of their contingency, the supreme imprint, that is to say the breath and hand of God; and so they are placed as the very archetypes of being.” It was Cézanne himself who proposed this metaphor in a 1903 letter to his art dealer Ambroise Vollard: “I am obstinately working; I am catching a glimpse of the Promised Land. Will I be like the High Priest of the Hebrews or shall I be allowed to enter?” Testori concluded: “Cézanne thus shows us that the love for truth can only be realised where the everyday and the usual (apples, for example) fall into their origin.”

It was not just Testori who had noticed the revealing novelty of the Parisian exhibition: even Peter Handke, the great German writer, later a Nobel Prize winner in 2019, had collected reflections from those visits in a small book The weight of the world. Handke had glimpsed in Cézanne the “possibility of describing the world: a sensation finally unites with an object.” For his part, Testori, with the impetus that distinguished him, had suggested investigating the opportunity offered by that exhibition, and the result was a notebook enclosed in that 1978 issue of CL Litterae Communionis, the movement's magazine that later became Tracce [Traces].

However, not only can Cézanne be identified in Testori’s Two Apples. Another artist he loved who made the apple the centre of some of his works that marked the art of the 1900s was Alberto Giacometti. In 1937, the Swiss artist, now in Paris, had painted a Still life with an apple, now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It is certainly one of his highest and most moving works. It shows a large cupboard in his birthplace in the Alps of Val Bregaglia, with a small apple on top. The apple seems a little lost in that much larger space. Yet it is the apple that gives the painting its title, to which Giacometti's probing eye points. There is a lot of love in this gaze that seeks out the object, respecting it in its smallness; there is a lot of love in these laborious, patient brushstrokes that advance without imposing certainties, without the presumption of 'succeeding' in finding what it is looking for. That is why in that apple, in addition to love, there is undoubtedly also a great deal of restlessness, as another famous writer, Jean Genet, had grasped when visiting Giacometti's studio. Referring to the objects painted by the artist, Genet wrote: “If they seem restless, it is because of their purity and uniqueness... the object painted by Giacometti moves us and reassures us not because it is more human – because it is used by man – but because it is 'this object' in all its defenceless purity of object... it is alone in its being, in its being irreplaceable.” In its poverty, the apple becomes an emblem of a beauty that originates from the wound of that restlessness. “Giacometti's art,” Genet writes, “seems to me to unveil the secret wound of every being and everything, so that the wound may illuminate them.”

Read also - Seamus Heaney: a portrait of the poet

The apples painted "with wide eyes" by Testori can therefore also be read as a homage or hymn to these two great artists. The homage of a writer so in love with painting that he himself wanted to attempt the adventure of this artistic form, as the possibility of a look at reality finally "freed from all false appearances " (Genet).