Trump, Vincenzina and the Forgotten Heart

Ten days after the United States presidential election, the main question remains, why have the “forgotten men” voted for Donald Trump? A reflection by Giorgio Vittadini.Ten days after the American elections, the main question remains: why have the “forgotten men” voted for Donald Trump? In reality, it appears ever more evident that the capitalist system in the last few years has brought a growing inequality between classes that society is no longer able to accept. There is the problem of joining, on the one hand, the creation of wealth to, on the other, a distribution of that wealth that is as equitable as possible.

If the economy is made by men and for men, the main thing to understand is that people are the real resource, not only to protect, but to keep in mind as the protagonists of society and thus of economic recovery. Not to understand this fact means provoking an inevitable unease, anger, and resentment that break out into what today is generally called populism.

During the industrial boom in Italy during the 60s, one could see the slow but steady change from an economy that was primarily agricultural and historically poor to a developing economy based first of all on industry and then on services. This development led to Italy’s entrance into the G7.

An amazing song by Enzo Jannacci, Vincenzina e la fabbrica [Vincenzina and the Factory], set in the Milan of those years, recounts the life of a woman excluded from the world of production, almost chained to the role of housewife, who from the gates observes the factory where her husband works. The factory was the hope of emancipation, the project of a better life for herself and her children, a better life obtained by hard work and political struggle.

For more than thirty years, this process seemed to be an unstoppable fact throughout the world. Then there followed de-industrialization, the downfall of Ford-ism, and the irruption of the new economy which pushed the capitalist model toward globalization at a forced march. In this process, the real economy has been neglected in favor of a financial system which is completely without rules. This has changed the world.

When the big factories started to close, much production was transferred to the Third World to save on the costs of labor, resulting in an authentic “dumping,” using immigrants as a substitute for a more organized and specialized manual labor force. What remains of the working class from the 1970’s, which was catered to by everyone and was going “straight to paradise”? They have simply been forgotten. Social disparities are more profound today in the third millennium than they were in the 19th century.

Today, 1% of the world population holds more wealth than the rest of it. A study done by Branko Milanovic, an economist from the World Bank, based on data from the Luxembourg Income Study, documents how the share of income of the middle class (about 30 to 70 percent) has diminished over the last 30 years by between one and four percent of the GDP in the major developed countries, depending on the country.

With the “affluent society,” American “blue collar” workers, like those in Europe, have lost income, not only relative to the wealthy, but also to citizens of emerging, developing countries. United to this is the impoverishment of what is called the middle class. A few concrete examples: in the United States, between 1980 and 2013, the middle class’s share of income decreased from 32 to 29 percent; in the United Kingdom from 33 to 32 per cent; in Germany from 34 to 32 percent; and in Canada from 33.5 to 31 percent.

These two forgotten classes, no longer thought to be politically relevant, have been abandoned by both the left and the centrists. Everyone has embraced the model of development dictated by finance and multinational companies, thinking it was sufficient to increase the wealth of one group, trusting in the market and demonizing any kind of public intervention in the economy.

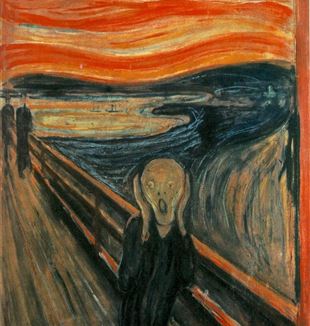

In front of this reality, it is a significant fact that the top 100 American businesses gave money to Hillary Clinton, and that she received the endorsement of nearly all the important newspapers (380 for Hillary vs. seven for Trump). Politics forgot about the “blue collar” workers. What is more, few remember that in order to finance Obamacare and health care for all, insurance companies raised prices for the middle class by three to four times. If we think about unemployment and about banks that tightened credit after the financial crisis, how can we be surprised by the shouts that became votes for Trump and other xenophobic parties? It is a desperate cry, “The Scream” by Munch, to which the populist movements respond, based on simplifications and banalizations, incapable of providing answers in the real world.

There is no longer an answer to the questions coming from the depths of society. What is it that is really needed? A recognition of people’s desire to work, to express themselves, to build, to be protagonists.

Vincenzina is not only a woman from the 1960’s. She is someone who notices the “smell of cleanliness” and of the labor that is done in the factory, who doesn’t like that “Rivera doesn’t call me anymore,” who perceives the sadness in daily life, who wears a scarf that is already out of fashion. But despite all of this, Vincenzina loves the factory. She loves the reality that provides work; she doesn’t look at what is lacking, but at what gives her the possibility to live and to go forward. This is what the dominant classes have forgotten: the heart of people with its irreducible desire for good, for a destiny that is happy and full of beauty, goodness, truth.

The task that we must face is difficult. It will need a long time to carry out. It is apparently without immediate results.

But whoever already lives in dialogue with his or her heart can hear the cry of the defeated ones, can walk with them, can rediscover what makes us love, fight, and constantly seek out a better future. After the industrial revolution, the whole world saw the birth of movements, intermediate organizations, unions, and popular political parties which sought out new roads for justice, equality, and the well-being of everyone. It is the same task that awaits us.

Previously published in Il Sussidiario, November 18, 2016