Called to Live For Him

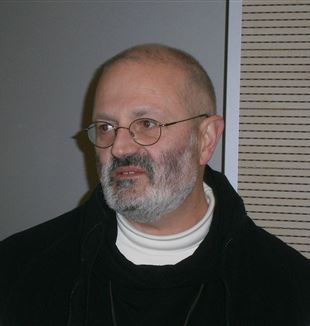

Face to face with Fr. Mauro Giuseppe Lepori, chosen to guide the 1,800 Cistercians scattered around the world, after 26 years in the monastery. He describes his "vocation within the vocation" that allowed him to discover "there's gusto in everything.""A second call"–with all the richness that phrase holds for a person who gave his life to Christ, entering the monastery over a quarter of a century ago. A native of Lugano in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino, in Switzerland, a monk since 1984 and Abbot of the Swiss Abbey of Hauterive since 1994, theologian, philosopher, and author of books translated in half the world, for five months now Fr. Mauro Giuseppe Lepori has been Abbot General of the Cistercian Order–at the age of 51, an unusually young age for such a responsibility. Above all, it is a revolution for him, finding himself catapulted from the canton of Fribourg to the center of Rome, in the General House where he guides an order spread to four continents (only Australia is missing), which he will explore and learn more about, populated by 1,800 monks and nuns. Yet he uses this expression, clear and simple, like all the words he uses economically, thinking well before answering: "a call." His is a vocation within a vocation, into which it is beautiful to excavate a bit, to understand what it means to live for Him, and Him alone–the essential. "It was very clear when they repeated my name during the counting of votes," explains Lepori, "that the issue wasn't that I was being elected, but that Christ was calling me. I felt Him strongly; I was moved and grateful."

What has it meant for you to come to grips with this "second vocation"?

I thought, "Here, the Lord is calling me again with an intensity I thought impossible." I felt Him like a fullness, an offer of greater life. Only by keeping alive this awareness is it possible to go forward without becoming a functionary. Otherwise, I run the risk of letting myself be determined by the requests of others and the things to do, more than His call. Instead, before Him, I can discover the freedom even to say "no." And I can realize that even certain arid things, some aspects of work you instinctively wouldn't want to deal with–some managerial questions, the organization–have life within.

Do you miss anything about Hauterive? Like the rhythm of life, certain relationships? After 26 years and 16 days as Abbot…

No. Actually, I'm surprised to find I'm not "in mourning" as I had expected. I remain very bonded with that community, to which I continue to belong, but I understand that I have to find community here, with the whole Order, but above all here, in the house. I won't be here much, because I have to travel a great deal, but as soon as I arrived in Rome I had a meeting with all the monks in the house, who are mostly students, and I told them, look, I don't want to live in a dormitory; I want to live in a community. In a community there are three dimensions to care for in particular: Fraternity, or, in other words, a communion that permeates everything: recreation, service, reciprocal attention. Then Liturgy, being united in acknowledging the mystery of Christ and celebrating it, an attention to having Him at heart. Finally, helping each other to deepen the Word: that there be a common teaching, communicating to each other what we listen to and what each of us lives, like experiences and studies–with all the challenges that entails! There are challenges because a Vietnamese and an American, for example, are very different. But it's a community, in all its aspects. Certainly, there's less silence than at Hauterive.

What makes a community? What are the essential factors, after those three points?At the chapter, I insisted on this a lot: we have to return to a true communion of life, not a simple "staying together." Today, there's a lot of individualism going around, a crisis in the relationship between the person and the community. Many religious are worried about other things, the scarcity of vocations, whether they should have a school or not, whether they should run a parish or not. All this depends on the circumstances, but the sine qua non that allows us to live our charism is that there be a community–unless someone is so experienced as to be able to live communion even alone.

What is the source of this individualism?

It comes from many aspects. Today even the State tends increasingly to address itself to the individual. And even communications seem custom-made for this: they end up incentivizing individualism a great deal. But that's not the heart of the question. The truth is that every century has asked the question in its own way. Benedict speaks of it throughout his Rule. And if you go back far enough, you get to Ananias and Sapphira, who defrauded the Apostles, pretending to belong to the community, but holding back their nest-egg. That's also individualism. So the problem has been there since the beginning of the Church. There, Peter reproved the two of them and said: you've lied to the Holy Spirit. It is an invitation to bring the problem all the way to the Mystery enclosed in the mystery of the Christian community, which is a participation in the Trinitarian Communion. The goal is not the community in and of itself: it is the community inasmuch as Christ, through the Holy Spirit, allows us to participate in the origin and end of all being. It's not voluntarism, a "we need to be communitarian." If someone asks, "Why should I sacrifice myself for the community?" I can't answer, "Because this is the way to love, this is the way not to be egotistical…" These are moralistic answers, and they're not enough. A contemplative dimension is necessary in order to live this challenge, the awareness of the Mystery. I sacrifice my individualism and I care about living in community because I want to live the communion between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. "As the Father has loved me, so I too have loved you." Christ offers us that love there, that communion. "Remain in my love." It is important to remind each other of this, above all in the monastic communities called to a life of memory.

Community Without Memory is Impossible…

True. Many expressions after the Council, but even before, depend precisely on this idea of community that, deep down, isn't Christian. Or they even depend on certain abuses of freedom, such that I expect you to renounce everything–or your freedom–for the community, but I don't offer you this dimension, this possibility of living everything for Christ, for participating in what Christ gives. Thus, it ends up that the community is an abuse, above all where it asks everything of you, like in a monastic reality. Instead, you overcome the toil only by re-proposing the fascination of the Mystery of Christ. When that is visible as experience, it attracts everyone, from all cultures or all eras. I am very challenged here, for example, because there are people from four continents, all very different from each other.

You used the adjective "arid" for some of the things you have to take charge of in your new function. It reminded me of a sentence of Fr. Giussani on work as "the most arid and toilsome aspect of the relationship with Christ." What are you discovering about yourself in dealing with this aridity?

I discover that there's gusto in everything, this is true. But only if I make memory of the vocation, of Christ who calls me through that. So then I understand that the reason is beautiful, and always positive. But "arid" can also be simply when you're in the airport waiting for a flight and you're tired and don't feel like reading… You always have to recover the reason: "I am following Christ. I am this way because He calls me. I pass through this, but this transforms everything." There's a kind of miracle that happens. All of a sudden, you understand the beauty.

What does it mean to "make memory of the vocation"? How do you realize that it's happening?

It means making memory of Christ present. And it's true that the arid things are a great help, because they challenge you. They obligate you more. In the things we like, it's easier to lose this sense. You can think that the things are enough for you, that you don't need this mysterious Presence. But it's always positive to pass through the deserts. And then, the arid things are the ones for which I don't see an outcome, that ask of me what I wouldn't like to do, wouldn't like to decide. Those are the things that bring you more to the question, to prayer, to entrusting everything to Him, because then He makes you an instrument of what He wants to do.

How is this provocation different or deeper than the "first vocation" when you entered the monastery?

I've had different types of calls, but if we want to simplify, the word that best describes my monastic vocation is in John 15:5: "Whoever remains in Me and I in him will bear much fruit." You ask whether a form of vocation will truly bear fruit in your life, and you're tempted to question a form that you encounter precisely on this aspect: will it truly give fulfillment to my life? Instead, when I was there to do my first month of trial, I didn't meditate on anything other than the first half of John 15, up to verse 17, with the awareness that for me, that was the place where I adhered to Christ: the fecundity was ensured by that. It wasn't a reasoning of my own anymore. You can be a monk, abbot, or bishop, but if you aren't united with Christ, you're not fruitful. Instead, if you follow the road Christ wants you on with Him, the fecundity is assured, and is constantly renewed. The vocation is Christ, not a thing. It's a relationship. The particular vocation of each person is that Christ has a place, a form in which He makes you understand: here you are united with Me. It's like a diapason, a tuning fork, to which, with the help of the Christian community, you can tune yourself, in order to stay bound to the origin, because that is the main issue: where do you find the lymph, the sustenance for your life?

What is the task of the Benedictines today?

Showing that the Christian life is a human life, and thus that it takes everything. It's not a vocation fixed on a specific task that is in function of something; it's a totality. The Rule of St. Benedict touches all of life, from the spiritual and sublime aspects to the more physical, material ones. And this is the most important task: demonstrating with life experience that Christianity embraces all our humanity, and does so in the degree to which you're faithful to certain dimensions: the community, prayer, work. There is a stability–that is, binding yourself to an incarnate place in which you are the one who has to change, not the place or the people. A true humanity always has to be educated. It's important that the monasteries that live the Rule offer this. Incarnate places.

What are the most urgent problems you're already beginning to work on?

With the premise that the fundamental point is communion, there's a work of recovery of freedom to be done. It's necessary to educate it and accompany it, patiently. Many problems in the Church come from this: from the freedom to belong. In staying together, there's always a bond, a dependence, but in freedom.

How do you educate to freedom?

Saint Benedict says that the abbot must give the monks a word that is "ferment of divine justice." A yeast. A teaching, an indication of the road are needed that are like yeast for the person. But then the person has to walk, freely. So when you announce the truth as present, fascinating for you now, then freedom is fermented, receives yeast. With freedom–and with time–the person can grow. Freedom is affirmed and educated above all by acknowledging it, helping people to see they have it.

What does that mean?

Sometimes, we don't even know what freedom means. We have a totally unbalanced concept of it. In order to show what true freedom is, first of all, it's important to live with the other, put yourself in relationship with him. I have to live in the community this way, trying to establish a relationship with them. The relationship manifests the fascination of freedom. Today in the Church, it's spoken of a lot, but often the words used are too moralistic to be fascinating: too many "you must" instructions. Instead, it is a beauty that attracts.

As Benedict XVI continually reminds us…

Precisely. Maybe in the long run it seems that nothing happens, but it's a yeast. It seems that nothing's changing, but it does change things.

What consonance is there between the Benedictine charism and that of CL? How did you discover it over time?

The Lord made me discover the consonance through different encounters. He has always given me a call and a place to live it. The call, the vocation, enflames you, but if you don't belong to a place that helps you to carry it and live it, all this becomes a remembrance. Instead, each time I realized that there was a call of the Lord, at the same time there was a place that enabled me to walk–from the very beginning. I discovered the unity between the experience of the Movement and the Cistercian one as I lived. I followed just one road. I discovered that Benedict is very present in Fr. Giussani; CL, in some way, re-proposes the Benedictine charism.

In what sense?

As an experience of humanity and as a method, that is, as places in which this experience of humanity becomes possible. And everything is centered on Christ present. In my life, this was the parabola.

And Fr. Giussani? Who is he, for you?

An encounter. Rare, in every sense of the word. I saw him only a few times, unlike other people who also marked my life, like Bishop Eugenio Corecco, of Lugano. But every time, it was full. He left his mark on me in his humanity, his gaze, and the true words he gave me. He remained impressed in my poor person, because it was, and remains, an encounter within the Great Encounter.