On The Side of the Common Good

Little more than a month has passed since Julián Carrón’s talk at the assembly of the Companionship of Works: “Your Work is a Good for All.” What has happened in the meantime.Little more than a month has passed since Julián Carrón’s talk at the assembly of the Companionship of Works, published in the last edition of Traces: “Your Work is a Good for All.” What has happened in the meantime–the world suffering even more in a spiral of pessimism and tensions, and with the economic crisis that has not yet slackened its grip–has, if anything, given more weight to those words.

He spoke of the risk of closing in on ourselves, of giving in to the difficulties and taking the way of “every man for himself” (“the insidious instinct of ‘every man for himself’ is stronger than ever,” Carrón said), to hold together the fragments of a chaos in which the others seem to be an obstacle to your own happiness. He stressed all the limitations of this individualism, which doesn’t really fill the heart and “is useless in resolving the drama of man.” Above all, he warned of the need to go to the root of the reasons which, almost mysteriously, enable many people not to give up. For there are many–even amongst the entrepreneurs present at that meeting, but not only–who don’t close in on themselves, forgetting others.

Those reasons were taken up again: the entry into the world of the only fact capable of answering man’s needs for totality, “Jesus of Nazareth, the Mystery become flesh,” the fact of His presence, now. And the superabundance of charity of which He has made us the object, which makes us unthinkably capable of gratuitousness, beyond all calculation. In order to take up this course again, we asked four people, very different from each other and engaged in different fields of work (a journalist, a philosopher, a professor of negotiation and conflict management and trained mediator, and a business analyst), to take up that road, and to measure themselves against Carrón’s words. We offer their answer as a starting point for a work that concerns us all.

Modern individualism is incapable of realizing the value of man. The (losing) alternative is a sentimental solidarity.

After Julián Carrón’s talk at the Companionship of Works (CDO) assembly, here are some points about need–our need and that of others. Is it true that the desire for satisfaction draws us toward others and makes us love them? Let’s start off from a very simple hypothesis, and then move on to the test of charity.

The question of charity is beset by many puzzles for the modern Christian. What does it mean to “love my neighbor”? And … “as myself”? Do I divide my possessions equally between us? If so, which neighbor do I choose for this division? And then, do I choose another neighbor with whom to divide what is left? And so on? What, then, about those to whom I have more immediate responsibilities? Must they suffer my philanthropy in silence?

The theological mind often brushes aside such questions in a barrage of sentimental injunctions. Hovering around modern Christianity is a lazy idea that you can simply translate the Gospel injunctions about poverty into economic doctrines and then forget about everything. Sometimes, indeed, one might get the impression that Christianity in a modern society is all but indistinguishable from socialism. More and more, we hear the name of Christ used by secular-atheist ideologues seeking to provoke Christians who, they say, fall short of their “Christian” obligations by failing to agree to radical redistributive policies.

The Two Coats

Might they have a point? In a social reality increasingly resembling a gigantic machine, does not this question of “love” not come down to, and end with, maintaining the correct political outlook? No, a cursory check reveals that, while urging that he who has two coats should give one coat away to one who has none, Christ did not say that we should give our spare coats to the State for redistribution to officially designated recipients.

Because of this element in Christianity of what seems like disapproval of personal wealth and possessions, the maintenance of material well-being can seem difficult to reconcile with a religious existence. Taken literally, the analogy of the camel and the eye-of-the-needle suggests that widespread poverty is the most “spiritual” option: only by remaining poor do we retain God’s favor. How, then, do I justify retaining the fruits of my efforts in a world unequal beyond my ability to influence or alter it?

The more the “traditional,” moralistic Christian drum is beaten, the more it drives individualized humanity back to the counting beads. For some, the irresolvable contradictions create a justification for withdrawal from the challenge that faith extends, an alibi for surrendering to the individualist pull: “I am not good enough; I will stop trying!”

The disparity of means even within a single prosperous society can mean that guilt forces the well-to-do into a choice not between keeping what they have or giving it to the needy, but between adhering to a faith that makes them uncomfortable or deciding that they no longer belong or believe. And these pressures are infinitely greater in the age of instantaneous globalized images of poverty, famine, and catastrophe. The spirit may be willing, but the flesh, being weak, has the stronger pull. The individualist retreat from religion, then, is in part the expression of what seems to be a rational self-interest: the desire to escape the contradictions between an acquired lifestyle and what Christ seems to be urging upon us.

Once faith has been even marginally weakened, the pull of the material is proportionately stronger, and this process is furthered by the continuing message from the open door of the Church, from which admonitions about “charity” pursue the departed doubter as he seeks refuge among his possessions. His response, clouded by guilt and self-righteousness (he works for his wages, after all!) is to become confirmed in his “unbelief.”

For those who remain, seeking to find a way through the guilt and sentimentalism, is love of neighbor merely a matter of feeling better? Can I “buy” peace of mind by giving to others? Somehow, this does not seem to be what Christ had in mind.

A complicating factor is that contemporary economies are not moral equations, but more like engines, which require particular forms of intervention to keep them functioning. The modern politician or economist deals not with zero-sum equations, but with phenomena that, if manipulated correctly, have the capacity to do something not entirely unlike the miracle of the loaves and fishes. Christian clerics often attack “conspicuous consumption,” “secular individualism,” and “greed,” but without either spelling out what these terms mean, or displaying any understanding of how the underlying mechanisms operate, or advancing an alternative set of economic mechanisms more in line with Christian teaching.

It is helpful, then, to know that there is a method and that, moreover, this method acknowledges the difficulties, sometimes explicitly and always, at the least, by implication.

Wolves and Rules

In his talk to the Companionship of Works National Assembly, Julián Carrón sets out the reasons to continue believing in the community of humans, to avoid the instinct to see the world as a matter of “every man for himself”–the option those paradoxes and puzzles edge us into.

In response to rational objections of the modern citizen, Father Julián offers a reasonable proposition: that individualism is not simply a “wrong” choice but one that goes against self-interest, because it ignores some of the factors at play in the human equation. It is therefore not a true solution, eliminating, as it does, a necessary tension between the “I’ and the “others,” and insinuating that individual happiness can be located in “things.” Thus, modernity displays yet again its inadequacy as an answer to human desire, multiplying the opportunities for individualist expression but multiplying also the rules which are needed to restrain “the wolf lurking in each of us.” Wolves, Father Carrón assures us, cannot be tamed by rules.

But neither are the answers to be found in a sentimental solidarity. Charity/love requires a movement, based on reason. It begins in the human heart, but must continually seek its harmony beyond usefulness or obligations. It reaches toward something greater, something felt but perhaps inchoate, an attraction toward beauty, truth, justice, but defined in us by a desire for belonging. Our need for friendship becomes the touchstone, and this is what should guard us against the impulse to create structural entities focused on power, success, and ideological belief, for these will not endure as friendship will.

Detached from “Things”

Could this be true? That out of the desire to satisfy his own needs in the deepest way, man can meet to the maximum Christ’s call to “love thy neighbor as thyself”? Wow! But, lest we get carried away with the simplicity of this, we are reminded that this is no ordinary affection. It is THE affection, the one born of the need for totality. And this becomes possible only by accepting Christ’s total gift of Himself, because only in Him is this total affection rendered visible. By coming and dying and rising again, He showed us the ideal in which we might find an echo of His grace, the model on which to base our own searches.

Without God’s love, we could not know how to love one another. Human love, charity, cannot exist without awareness of God, of the gestures, gifts, and presence of Christ.

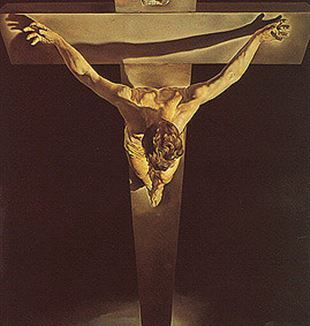

This seems to be the key to understanding why traditional, moralistic approaches to “Christian” charity do not seem to work. We do not love one another because Christ told us to, but because He loves us and thereby enables us to love abundantly. The Cross reminds us that Christ’s love transcends pain and loss and death, because it bears witness to the fact of redemption. Becoming aware of His presence, I am freed to give of myself, knowing that no true gesture or gift will be wasted or lost. Only in this way can individualism be defeated, because this path is the one that allows our fingers to be pried from the things to which they cling for fear of some undefined and unnamed want.

And here, Carrón, citing Giussani, brings us in front of an insight into how the fabric of our lives might be altered to provoke this new relationship with reality, dissolving the puzzles and making the path clear. Yes, I should work at my projects and the betterment of my own and my family’s lives–but in doing so seek an imitation of Christ, which will enable in me an impulse directed at my neighbor’s needs. This is true charity.

And, if I understand correctly, the true test of this is that it will bear all the appearances of gratuitousness. It will offer no objective justification of itself, will not explain itself in moral terms, will seem, on the face of itself, to be a kind of madness. Only in this way will my gestures alert the observer to the presence of Something Else, and only this Something Else can truly deliver what any of us desires.

“Man does not live by bread alone.” We have heard that message ten thousand times. But each time we miss the “alone,” or see it from one angle only. In Communion we eat the bread together, and for a reason: we share what matters between us–and taste, perhaps faintly at first, that which we truly desire.