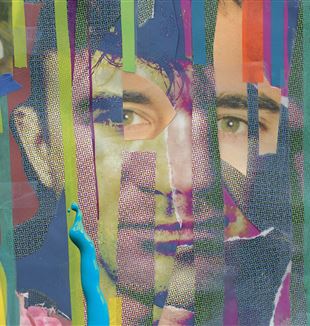

Sufjan Stevens: An angel with a banjo

In his songs he quotes Flannery O'Connor, he is a believer but does not want to "impose a religious content on anything I do" because the important thing is that "faith lives." A portrait of a great uncategorizable American singer-songwriter.Sufjan Stevens is one of the most important American singer-songwriters. He does not have a contract with a major label, but releases his records with his own record company called Asthmatic Kitty. Technically, he is an indie songwriter (short for independent). This has not prevented him from having international success, appearing on Jimmy Fallon's 'Late Show' and gracing the stage at the 90th Academy Awards ceremony to sing Mystery of Love, for which he had received a nomination. All very mainstream stuff, the opposite of indie.

Another reason why the attention he received from the media and the general public is strange is that Stevens does not hide his Christian faith that often emerges in his song lyrics. The title of his latest song, Javelin, is a quotation from a short story by Flannery O'Connor, itself a reference to Teilhard de Chardin’s Everything That Rises. One of the verses goes: "Jesus lift me up to a higher plane / Can you come here before I go insane? / Cast me not in hell, where the demons rage / Turn yourself around to see what I can say." These words are explicit but, as we shall see later, his work has nothing to do with American Christian Music, made up of easy biblical refrains.

Stevens is a very prolific songwriter: in his almost 25-year career (he was born in 1975) he has released 18 albums. Nine were recorded in the studio, one live, two collections of Christmas songs, and six instrumental or collaborative works with other artists. His first great success came in 2003 with Greetings From Michigan, The Great Lake State, an album dedicated to the American state where he was born.

Two years later came Sufjan Stevens invites you to: Come On Feel The Illinoise (a pun on Illinois and noise). Word got out that the singer wanted to write an LP for each of the states of the Union. Which never actually happened. The songs are about places, historical figures (such as serial killer John Wayne Gacy Jr), childhood memories or sightings of ufos. In Chicago he sings: “I drove to New York / in a van, with my friend / We slept in parking lots/ I don't mind, I don't mind / I was in love with the place / In my mind, in my mind / I made many mistakes.”

Stevens' style is marked by his unmistakable falsetto voice which, instead of being cold (as for example, that of the Bee Gees), is warm and mellow. His melodies are often sharp. Arpeggios of acoustic guitars. The metallic sound of the banjo. Background choruses. Woodwinds. The appearance of a piano. The atmospheres are often gentle, sometimes languid. His lyrics are intimate, poetic, in many cases cryptic. His choruses are obsessively repeated like mantras. Over time, a lot of electronic music has also featured, like in The Age of Adz, a beautiful album that ends with a crazy 25-minute long piece entitled Impossible Soul: five songs that merge into a single suite, at times sweet and at times obsessively hypnotic. However, his most personal and mournful track is Vesuvius: "Sufjan / Follow your heart / Follow the flame or fall on the floor/ Sufjan, the panic inside / The murdering ghost that you cannot ignore.”

But the summit of his work, at least so far, is a record from 2015, Carrie & Lowell, dedicated to his mother – who had recently died at the time – and to the relationship between Stevens and his mother’s second husband, who became one of the founders of Asthmatic Kitty. Stevens was raised by his father, Rasjid, and his stepmother, Pat, only having the opportunity to occasionally visit his mother Carrie, who struggled with depression and alcoholism all her life. In Death With Dignity he sings: “I forgive you mother, I can hear you / And I long to be near you / But every road leads to an end / Your apparition passes through me, in the the willows.” And, in the very sweet and heartbreaking Fourth of July he says: "The evil it spread like a fever ahead/ It was night when you died, my firefly / What could I have said to raise you from the dead? / Oh could I be the sky on the Fourth of July?"

Then there is that mysterious and poignant song called John My Beloved (yes, the reference is to the disciple whom Jesus loved): “So can we pretend, sweetly / Before the mystery ends? / I am a man with a heart that offends / With its lonely and greedy demands / There's only a shadow of me; in a matter of speaking, I'm dead.”

Stevens dedicated his last record, Javelin, to his friend who died a few months ago. In fact, the common thread is the journey into the experience of a troubled love, far removed from a romantic idyll: laden with all the work, weight and fatigue of being compared with to the other daily. Love that ends. Love that lasts. In Will Anybody Ever Love Me? he sings: "Chase away my heart and heartache / Run me over, throw me over, cast me out / Find a river flowing to the west wind / Just above the shore line, you will see a cloud.” And the chorus answers: "In every season pledge allegiance to my heart / My heart burning / My burning heart / My burning heart.” Genuflecting Ghost, on the other hand, begins: "Give myself as a sacrifice/ Genuflecting Ghost, I kiss the floor / Rise, my love, show me paradise/ Nothing seems so simple any more.”

At the beginning it was mentioned that Stevens is a Christian and often makes this clear even in his lyrics. More precisely, he is a believer in the Anglo-Catholic Episcopal Church (like T.S. Eliot). Yet, listening to his songs, something does not add up. Or, at least, it does not correspond to what we would normally expect from a 'Christian singer'. To a journalist who asked him if "being an artist of some repute" he found it uncomfortable having to spread "the Good News", he replied: "Not necessarily, you know. I think the Good News is about grace and hope and love and a relinquishing of self to God. And I think the Good News of salvation is kind of relevant to everyone and everything.” The reporter was incredulous. And he pressed him with questions about corruption in the Church and its dogmatic approach. Stevens retorted: " What’s the basis of Christianity? It’s really a meal, it’s communion right? It’s the Eucharist. That’s it, it’s the sharing a meal with your neighbors and what is that meal? It’s the body and blood of Christ. Basically God offering himself up to you as nutrition. Haha, that’s pretty weird. It’s pretty weird if you think about that, that’s the basis of your faith. You know, God is supplying a kind of refreshment and food for a meal. Everything else is just accessories and it’s vital of course, baptism and marriage, and there’s always the sacraments and praying and the Holy Spirit and all this stuff but really fundamentally it’s just about a meal.”

Read also - Indestructible, stubborn presence

Stevens knows his stuff and you can see that he has not completely forgotten the Catechism. Yet he rejects the label of 'Christian' artist. The relationship with his faith, he says, is not extrinsic to what he does as an artist, but is the sap that nourishes and makes his art alive. He explains in fact: "I believe that, from a technical point of view, my artistic process is guided less by the abstractions of faith or politics and more by practical theory: composition, balance and colour.” In other words, his concern is to make good music that works first and foremost as music. He adds: "It’s not so much that faith influences us as it lives in us. In every circumstance (giving a speech or tying my shoes), I am living and moving and existing. This absolves me from ever making the embarrassing effort to gratify God (and the church) by imposing religious content on anything I do.”

Hence the difficulty in 'baptising' Stevens' songs, which, even when they quote the Bible or the Gospel, never do so in a way to contribute to what Baustelle would call 'anaesthetic aesthetics', so common in contemporary Christian culture. It is poetry that keeps us on edge. In him there is a confidence in the persuasive and cognitive power of art that allows him to offer a contribution to the soul of a believer as well as to that man who is naturally, and often unconsciously, religious.